| THE HANDSTAND | AUGUST-OCTOBER2009 |

The Great Himalayan Watershed: Water Shortages, Mega-Projects

and Environmental Politics in China, India, and Southeast

Asia

"According

to a 2006 U.N. report, Asia has less fresh water than any

other continent other than Antarctica. In that light,

water is emerging as a key challenge for long-term Asian

peace and stability.

Although water covers two-thirds of Earth, much of it is

too salty for use. Barely 2.5 percent of the world's

water is potentially potable, but two-thirds of that is

locked up in the polar icecaps and glaciers. So, less

than 1 percent of the total global water is available for

consumption by humans and other species.

These freshwater reserves are concentrated in mountain

snows, lakes, aquifers and rivers. Already, 1.5 billion

people lack ready access to potable water, and 2.5

billion people have no water sanitation services."

http://japanfocus.org/-Kenneth-Pomeranz/3195

Kenneth Pomeranz

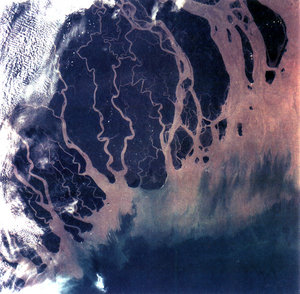

Ganges

Delta

Ganges

Delta

Since we tend to take water for granted, it is almost a bad sign when it is in the news; and lately there have been plenty of water-related stories from South, East, and Southeast Asia. They have ranged from the distressingly familiar -- suicides of North Indian farmers who can no longer get enough water1 – to stories most people find surprising (evidence that pressure from water in the reservoir behind the new Zipingpu dam may have triggered the massive Sichuan earthquake last May).2 Meanwhile, glaciers, which almost never made news, are now generating plenty of worrisome headlines.

Conflicts over water are found in every era and region: the English word "rivalry" comes from a Latin term for "one who uses the same stream as another." And more recently, questions about who gets to exploit water have become intertwined with questions about where the technological and ecological limits of our ability to do so lie – or should lie.

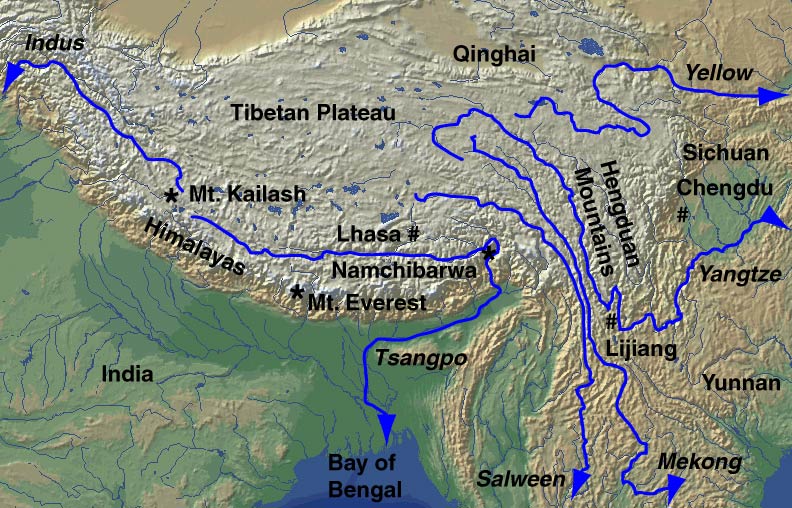

Nowhere are the stakes higher than in the Himalayas and on the Tibetan plateau: here the water-related dreams and fears of half the human race come together. Other regions have their own conflicts: the Jordan, the Tigris, the Colorado, and the Parana are just a few of the better-known cases where multiple states make societies make claims on over-stressed rivers. But no other region combines comparable numbers of people, scarcity of rainfall, dependence on agriculture, tempting sites for mega-projects, and vulnerability to climate change. Glaciers and annual snowfalls in this area feed rivers serving 47% of the world's people;3 and the unequalled heights from which those waters descend could provide staggering amounts of hydropower. Meanwhile, both India and China face the grim reality that their economic and social achievements -- both during their "planned" and "market" phases – have depended on unsustainable rates of groundwater extraction. As hundreds of millions face devastating shortages and the technical and financial power of these states (and of some of their smaller neighbors) increase, plans are moving forward for harnessing Himalayan waters through the largest construction projects in history. Even when looked at individually, some of the projects carry enormous risks; and even if they work as planned, they will hurt large numbers of people as they help others. (Nor is it at all clear that many of them will help as much as spending comparable sums on less heroic measures, such as fixing leaky pipes or tightening enforcement of wastewater treatment standards, would do.) Looked at collectively – as overlapping, sometimes contradictory demands on environments that will also feel some of the sharpest effects of global warming over the next several decades – their possible implications are staggering.

The projects to manipulate Himalayan water now completed, planned or underway are numerous, and their possible interactions are complex. And since many of the agencies responsible for them are far from transparent, the possible scenarios quickly multiply to a point where they are almost impossible to keep track of. But some basic – and frightening – outlines do emerge if we start from China – which is, for various reasons, the most dynamic actor in the story -- and then move across the lands that border it to the Southwest, South, and Southeast.4

China's Water Woes and the Push to the Southwest

Water has always been a problem in China, and effective control of it has been associated with both personal heroism and legitimate sovereignty for as far back as our records go – or perhaps even further, since the mythological sage ruler Yu proved his right to rule by controlling floods. But water scarcity has probably been an even greater problem than excesses, especially in the modern period. Surface and near-surface water per capita in China today is roughly 1/4 of the global average,5 and worse yet, it is distributed very unevenly. The North and Northwest, with about 380 million people (almost 30% of the national population)6 and over half the country's arable land, have about 7% of its surface water, so that its per capita resources are roughly 20-25% of the average for China as a whole, or 5-6% of the global average; a more narrowly defined North China plain may have only 10-15% of the per capita supply for the country as a whole, or less than 4% of the global average.7 Northern waters also carry far heavier sediment loads than southern ones – most readings on Southern rivers fall within EU maxima for drinking water, while some readings on the middle and lower Yellow River, and the Wei and Yongding Rivers are 25 -50% of that level; water shortages are such that Northern rivers also carry far more industrial pollutants per cubic meter, even though the South has far more industry.8 Northern China also has unusually violent seasonal fluctuations in water supply; both rainfall and river levels change much more over the course of the year than in either Europe or the Americas. North China's year to year rainfall fluctuations are also well above average (though not as severe as those in North and Northwest India). While the most famous of China's roughly 90,000 large (over 15 meters high) and medium-sized dams are associated with hydro-power -- about which more below -- a great many exist mostly to store water during the peak flow of rivers for use at other times.

The People's Republic has made enormous efforts to address these problems – and achieved impressive short-term successes that are now extremely vulnerable. Irrigated acreage has more than tripled since 1950 (mostly during the Maoist period), with the vast majority of those gains coming in the North and Northwest. It was this, more than anything else, that turned the notorious "land of famine" of the 1850-1950 period into a crucial grain surplus area, and contributed mightily to improving per capita food supplies for a national population that has more than doubled since 1949. Plentiful water supplies made it possible for much of northern China to grow two crops a year for the first time in history (often by adding winter wheat, which needs a lot of water); and plentiful, reliable supplies of water were necessary to allow the use of new seed varieties and plenty of chemical fertilizer (which can otherwise burn the soil). And, of course, irrigation greatly reduced the problem of rain coming at the wrong time of year, or not coming at all some years. During the previous two centuries farming in northern China had become steadily more precarious in part because population growth had lowered the water table – early 20th century maps show much smaller lakes than 150 years earlier, and there are many reports of wells needing to be re-drilled at great expense – and in part because the safety net the Qing had once provided fell apart. But beginning in the 1950s, and especially in the 1960s (after the setbacks of the Great Leap Forward) things turned around very impressively.

Much of that turnaround, however, relied on very widespread use of deep wells, using gasoline or electrical power to bring up underground water from unprecedented depths.9 Large-scale exploitation of North China groundwater began in the 1960s, peaked in the 1970s at roughly 10 times the annual extraction rates that prevailed during 1949 -1961, and has remained level since about 1980 at roughly 4 times the 1949-1961 level.10 But this amount of water withdrawal is unsustainable. The North China water table has been dropping by roughly 4-6 feet per year for quite some time now, and by over 10 feet per year in many places; some people estimate that if this rate of extraction is maintained, the aquifers beneath the plain will be completely gone in 30-40 years.11 This is by no means a unique situation; in the United States, for instance, the Ogallala Aquifer -- which lies beneath portions of western South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, and eastern Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico -- is being depleted at roughly the same rate. (Serious excess withdrawals began there in the 1950s, and as in China, turned areas previously marginal for farming -- the land of the 1930s Dust Bowl – into a breadbasket.) But consider the following: while the 175,000 square miles served by the Ogallala Aquifer are home to less than 2 million people, the 125,000 square miles of the North China plain were home to 214,000,000 people in 2000 (80% of them rural).12 The 2008 North China drought – the worst since the late 1950s drought that exacerbated the Great Leap famines – focused global attention on the problem for a brief moment, but chronic water shortages – both in cities and in the countryside – have been a fact of life for years, and conflicts over scarce and/or polluted water have become common events.13 So what is to be done?

China-India population density map

One hears periodically about various ways water is used inefficiently by urbanites; the Chinese steel industry, for instance, uses about twice as much water per ton produced as steel-makers in the most technologically advanced countries (though the Indian steel industry, for instance, is considerably worse than China's on this score).14 Leaky pipes and other fairly straightforward infrastructure problems create considerable waste. But relatively speaking, industrial and urban residential losses are small potatoes; agriculture still uses at least 65% of all water in China (though less, even in absolute terms, than 20 years ago) and has by far the lowest efficiency rates.15 Moreover, urbanites are sufficiently prosperous that price increases – unless they are very large – are unlikely to cause them to cut back on use very much. Certainly this is not where the most water waste is in commercial terms. According to some estimates, a marginal gallon of water sent from the countryside to Tianjin produces as much as 60 times as much income in its new urban locale as it did in the countryside.16 The best hope in terms of moderating China's overall water demand pressure is probably to keep per capita urban use from growing very much while water use efficiency and living standards there continue improving, and urban population grows sharply. Any significant reductions will have to come from the countryside. That process has begun, but it is unclear how far it can go without devastating social consequences.

A great deal of water is wasted in agriculture, in part because costs to farmers are kept artificially low; and since many rural communities have no way to transfer water to those who would pay more for it, anyway, "waste" has very little short-run opportunity cost for them.17 But it is worth noting here that "waste" has different meanings depending on what time frame one adopts. Irrigation water that never reaches the plants' roots and seeps back into the soil is wasted in the short term – it can't be used for anything else that year. But in the long term, it can help recharge the local aquifer. On the other hand, polluted water that could be re-used if treated properly but instead flows out to sea untreated is wasted in both senses, and thus represents a bigger problem. Chinese agriculture is not necessarily more wasteful in this regard than agriculture in many other places – and the deviations from market prices are no worse than in much of the supposedly market-driven United States – but its limited supplies make waste a much more pressing problem. ...

South-North water diversion plans

The project carries uncertainties commensurate with its size and cost. Among other things, there is considerable uncertainty about how dirty southern waters will be by the time they arrive in the north; diversions on this scale change flow speeds, sedimentation rates, and other important rates in unpredictable ways, and the original plans have already been modified to add more treatment facilities than were originally thought necessary. (Changes in water volume will also affect the ability of other rivers to scour their own beds – effects on the Han River, one of the Yangzi's largest tributaries, are a particular concern.) Conveyance canals passing through poorly drained areas may also raise the water table and add excess salts to the soil – already a common problem in irrigated areas of North China – and salt water intrusion rates in the Yangzi Delta.21 For better or worse, we will begin learning about the effects of the Eastern line soon, and probably about the Central line in just a few years.

But despite its long time horizon, it is the Western line – along with other projects in China's far west -- which is the big story. First of all, it offers the most dramatic potential rewards. The idea is that it will tap the enormous water resources of China's far Southwest – Tibet alone has over 30% of China's fresh water supply, most of it coming from the annual snow melt and the annual partial melting around the edges of some Himalayan glaciers. These water resources are an aspect of the Tibet question one rarely hears about, but the many engineers in China's leadership, including Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, are very much aware of it. (And ordinary Chinese are increasingly aware of it too – advertisements for bottled Tibetan water now adorn the backs of passenger train seats and other common locations, offering an icon of primitive purity of a type long familiar to Western consumers.) And hydro projects in this very mountainous region offer enormous potential rewards in electricity as well as in water supply. How much electricity water can generate is directly proportional to how far it falls into the turbines: the Yangzi completes 90% of its drop to the sea before it even leaves Tibet to enter China proper, and the Yellow River 80% of its decline before it leaves Inner Mongolia.22 On April 21, the Chinese government announced plans for 20 additional hydro projects on the upper Yangzi and its tributaries; if they are all completed, they would theoretically add 66% to the already existing hydropower capacity on the river (which includes Three Gorges).23

But secondly, the western route also poses by far the biggest complications. It is here that the engineering challenges are most complex and the solutions most untested. It is here (and in nearby Yunnan) that the needs of agrarian and industrial China collide most directly with the lives of Tibetans, Yi, Miao, and other minority groups. It is here that the environmental risks of dam building become major international issues, with enormous implications for the Mekong, Salween, Brahmaputra and other rivers relied on by hundreds of millions of South and Southeast Asians. And it is here that major water projects – which always include many uncertainties – collide with what has always been an extraordinarily fragile environment, and one which now faces far more than the average amount of extra uncertainty from climate change: Tibet, home to by far the largest glaciers outside the two polar regions, is expected to warm at twice the average global rate during the 21st century.24

Tibetan Rivers

State-building and Dam-building in the Himalayas

From the 1950s to the mid-1980s, China built plenty of dams, but relatively few of them were in the far west. This may seem surprising, given the concentration of hydro potential in that region, but makes perfect sense in other terms. The need to maximize energy production was less urgently felt before the boom of the 1990s, and there was much less concern about relying on coal (which still provides 80% of China's electricity25). Many of the dams that were built were constructed by mobilizing large amounts of labor (especially off-season peasant labor) in place of scarce capital, and it was a lot easier to use that labor close to home than to send it far away. The supporting infrastructure (e.g. roads) and technology for dam building in remote mountain locations was not available; the far reaches of the upper Yangzi were not even surveyed until the late 1970s. And the government was much more ambivalent about rapid development in the far west than it is today, with some leaders prioritizing more paternalistic policies that would avoid radical cultural change as the best formula for assuring political stability in the region.

But in the last two decades, all of this has changed, leading to a sharp shift towards the building of huge dam projects in Yunnan and Tibet above all. The technical capacities and supporting infrastructure needed for capital-intensive projects in these areas are now available; the pressure to increase domestic supplies of energy (and other resources, including of course water) has become intense; and the regime has clearly decided that raising incomes in the far west is the best way to keep control and make use of those territories – even if the wrenching cultural changes, massive Han immigration, and severe inequalities accompanying this development increase conflict in the short to medium term. For better or worse, a kind of paternalism in western frontier policy dating back to at least the Qing (albeit one that has long been gradually weakening) is now being discarded quite decisively. Meanwhile, changes in the relationships among the central government, provincial governments, and private investors have helped create enormous opportunities to gain both power and profit through accelerated dam building.

Plans to "send western electricity east," with a particular focus on developing Yunnan hydropower for booming Guangdong, date back to the 1980s; seasonal deliveries of power began in 1993.26 ...

Tibetans and other ethnic minorities in the far Southwest are likely to be the most affected. An unconfirmed report by the Tibetan government-in-exile says that at least 6 Tibetan women were recently shot by security forces as they protested a hydro project on the Tibet/Sichuan border.33 ...

The Other Side(s) of the Mountains: Pakistan, India, Nepal, Burma, Vietnam

Of course, people and governments further downstream also use rivers that start in the Himalayas – and many have plans to do so much more intensively. Many of them are very worried about Chinese initiatives that may preempt their own current or future water usage.

On December 9, 2008, Asia Times Online reported that China was planning to go ahead with a major hydroelectric dam and water diversion scheme on the great bend of the Yalong Zangbo River in Tibet.38 The 40,000 megawatt hydro project itself raises huge issues for Tibetans and for China. But what matters most for people outside China is that the plan not only calls for impounding huge amounts of water behind a dam, but also for changing the direction that the water flows beyond the dam – so that it would eventually feed into the South-North diversion project. The water that would be diverted currently flows south into Assam to help form the Brahmaputra, which in turn joins the Ganges to form the world's largest river delta, supplying much of the water to a basin with over 300 million inhabitants. While South Asians have worried for some time that China might divert this river, the Chinese government had denied any such intentions, reportedly doing so again when Hu Jintao visited New Delhi in 2006. However, rumors that China was indeed planning to begin such a project soon continued to circulate. (As we will see later, some Indian essays published in 2007 already assumed that China would make a major diversion from the Brahmaputra, citing this as a reason for India not to proceed with its own plan to transfer water from the Brahmaputra to other river basins south and west of it.) Indian Prime Minister Singh reportedly raised the issue during his January 2008 visit to Beijing, but a December, 2008 report from Asia Times Online said that China provided no assurances this time, and is in fact planning to divert the river. (No public statement was made at that time, but fewer official denials have been issued; the latest came former water minister Wang Shucheng on May 26, 2009.) Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao has said that water scarcity is a threat to the "very survival of the Chinese nation." Interestingly, unconfirmed reports back in 2000 had suggested that Beijing had already decided to go ahead; but not until 2009, when the Three Gorges would be completely finished.39

Water is indeed a matter of survival – not only for China, but for its neighbors. Most of Asia's major rivers – the Yellow, the Yangzi, the Mekong, Salween, Irrawaddy, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Sutlej, and Indus – draw on the glaciers and snowmelt of the Himalayas, and all of these except the Ganges have their source on the Chinese side of the border in Tibet. In many of these cases, no international agreements exist for sharing the waters of those rivers that cross borders, or even sharing data about them. ...

India, like China, has both extremely dry areas and some with plenty of water; and, as we have seen, it is also like China in that it is currently mining groundwater to produce important grain surpluses in some of these dry areas. So it may be no surprise that, like China, it is also contemplating a major scheme for diverting water from some river basins to others. The most ambitious, Himalayan, part of its Interlinking of Rivers Project would move water from the upper parts of the Ganges, Yamuna (a major tributary of the Ganges) and Brahmaputra Rivers westward, ending in the Luni and Sabarmati Rivers in Rajahstan and Gujarat. (Other Northwestern areas that would receive water are in Haryana and Punjab; a second, Peninsular, part of the project would mostly direct water to dry parts of Orissa and Tamil Nadu.) And just as China seems to be retreating from its earlier representations to India that it had no plans to divert water from the Yalong Zangbo/Brahmaputra, so this project suggests that India is hedging on its formal promises to Bangladesh (including a written understanding from 1996) that no water would be diverted away from the Ganges above the barrage at Farakka (a few kilometers from the India/Bangladesh border).70 ...

Late in January, Jiang Gaoming of the Chinese Academy of Sciences released a sobering piece (China Dialogue, January 22, 2009, link) about how accelerating the construction of dams in China's Southwest – part of the P.R.C.'s ambitious stimulus package to fight the global recession – is worsening the already considerable environmental and social risks involved, with some projects beginning before any Environmental Impact Assessments have been completed. Protests against Three Gorges by some leading scientists and engineers did not stop that project;108 it remains to be seen whether they will have more effect in the future. Recent reports that some poorly built dams on the Yellow River in Gansu – and perhaps many others elsewhere in China – are in dire need of repair109 -- may strengthen people, both within and outside the government, who are urging a more cautious approach to further mega-projects, but the outcome of such arguments remains unclear.

In short the possible damage to China's neighbors from this approach to its water and energy needs is staggeringly large – and the potential to raise political tensions is commensurate. Previous water diversion projects affecting the source of the Mekong have already drawn protests from Vietnam (and from environmental groups), and, as noted above, a project on the Nu River (which becomes the Salween in Thailand and Burma) which was suspended in the face of significant domestic and foreign opposition in 2004 and then re-started, has recently been halted again by order of Prime Minister Wen Jiabao.110 But some projects now underway or being contemplated have considerably larger implications, both for Chinese and for foreigners. The diversion of the Yalong Zangbo – if that is indeed on the agenda – would have the largest implications of all. If the waters could arrive in North China safely and relatively unpolluted – by no means sure things -- and having generated considerable power along the way, the relief for China's seriously strained hydro-ecology would be considerable. On the other hand, the impact on Eastern India and Bangladesh, with a combined population even larger than North China's, could be devastating. The potential for such a project to create conflicts between China and India –and to exacerbate existing conflicts over shared waterways between India and Bangladesh – is gigantic. ...

This article was written for The Asia-Pacific Journal and for New Left Review where it appears simultaneously. The version here includes the complete notes, maps and illustrations.

Recommended citation: Kenneth Pomeranz, "The Great Himalayan Watershed: Water Shortages, Mega-Projects and Environmental Politics in China, India, and Southeast Asia," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 30-2-09, July 27, 2009.

Three Gorges River, Yinchang

Notes

1 Sean Daily, "Mass Farmer Suicide Sobering Reminder of Consequences of Water Shortages," Belfast Telegraph, April 15, 2009, re-posted here.

2 On Zipingpu and the earthquake, see Sharon La Franiere, "Possible Link Between Dam and China Quake," New York Times, February 6, 2009,; Richard Kerr and Richard Stone, "A Human Trigger for the Great Quake of Sichuan," Science 323: 5912 (January 16, 2009), p. 322, summarizing both Chinese and American papers suggesting this. See also "Early Warning" a [piece by Evan Osnos of the New Yorker about the Chinese Engineer Fan Xiao, who had warned of such a possibility and was one of the first to suggest publicly that it had actually happened: February 6, 2009. A number of scientists had warned several years ago that the reservoirs of the Three Gorges Dam might trigger earthquakes, though on a much smaller scale than the quake that Zipingpu may have caused. See Gavan McCormack, "Water Margins: Competing Paradigms in China," Critical Asian Studies 33:1 (March, 2001), .p. 13

3 Sudha Ramachandran, "Greater China: India Quakes Over China's Water Plan," Asia Times Online, December 9, 2008.

4 For reasons of brevity, I am omitting rivers that flow east or northeast from the Tibet-Qinghai Plateau and wind up in Central Asia.

5 See for instance "Experts Warn China's Water Supply May well Run Dry," South China Morning Post, September 1, 2003, available here. ...

23 Calculated from data in "China To Build 20 Hydro Dams on Yangtze River," Associated Press, April 21, 2009, distributed by China Dams List, internationalrivers.org

24 Timothy Gardner, "Tibetan Glacial Shrink to Cut Water Supply by 2050," Reuters, January 6, 2009, citing the glaciologist Lonnie Thompson.

25 Keith Bradsher, "China Far Outpaces US in clearer Coal-Fired Plants," New York Times, May 11, 2009.

26 Darrin Magee, "Powershed Politics: Yunnan Hydropower Under Great Western Development," China Quarterly 185 (March, 2006), p. 25

27 Magee, p. 26; Grainne Ryder, "Skyscraper Dams in Yunnan: China's New Electricity Regulator Should Step In,' Probe International Special Report, May 12, 2006, page 3, available here.

28 Magee, p 35. For a useful timeline of China's electrical power reforms, see John Dore and Yu Xiaogang, "Yunnan Hydropower Expansion" (working paper Chiang Mai University's Unit for Social and Environmental Research and Green Watershed, Kunming, March 2004), p. 13. ...