| THE HANDSTAND | FEBRUARY-MARCH2010 |

SCIENCE ARTICLES

OF NOTE:

Meet Peter Higgs

The Man Behind The God Particle

By Margriet van der Heijden

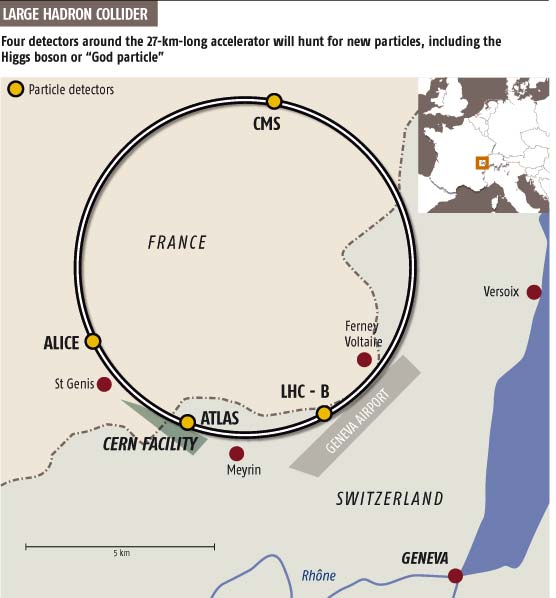

The Large Hadron Collider accelerator in Geneva was constructed to search for the Higgs boson, among other things.

Inside the walls of NIKHEF, the Dutch institute for nuclear research in Amsterdam, a group of renowned Dutch physicists have joined Peter Higgs in the cafeteria. Higgs is in town for the premiere of the Dutch documentary "Higgs, Into the Heart of the Imagination."

Higgs, who is 80, has become world famous because of the subatomic particle bearing his name, the so-called Higgs boson. Thousands of physicists are now chasing after the elusive particle at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva. The quest prompted the construction of the Large Hadron Collider, the most powerful particle accelerator on the planet, which cost more than €6 billion to build.

Did the idea that would lead to the discovery of the Higgs boson just pop into his head in 1964? "No," Higgs says, munching on a cheese sandwich and sipping orange juice. "That is not how it went."

His ideas formed more gradually, he says. "By the summer of 1964 I knew I was on to something. That was perhaps the reason -- because my head was full of thoughts -- that I forgot the instructions for putting up the tent when we went for a camping trip in the Scottish mountains."

A Fruitful End to a Dreary Holiday

Typically for Scotland, it was raining cats and dogs. The couple holed up in a bed and breakfast, and returned home earlier than intended. "I was pleased to get back," Higgs recalls. Back at the University of Edinburgh, he wrote the article that would make him world famous. "But I wasn't walking around shouting 'eureka,'" Higgs says, taking another bite out of his sandwich.

Physicists often refer to the Higgs particle, which is nicknamed the "God particle," as the pinnacle of the so-called Standard Model. That model describes the smallest particles of which all discernable matter in the universe is composed: stars, planets, people and atoms.

The Higgs particle might explain why so many of those particles have mass, causing them to move slowly and stick together, unlike the wispy photons that shoot through space at the speed of light.

Because Higg's theory is so complicated, metaphors have been invented to describe it. "Spontaneous broken symmetry," for instance, has been compared with the asymmetries caused by fibres and veins running through wood. Particles travelling along the lines of the veins experience little or no resistance, while those travelling at a perpendicular angle are slowed down, becoming heavy, like the matter of which stars and people are constructed.

Another metaphor is that of the US president making his entry at a party. When Barack Obama -- representing, in this analogy, a very heavy particle -- enters the room, the commotion caused by his arrival -- the Higgs boson -- spreads quickly and draws everybody in his direction. Because of all the people now flocking around him -- the Higgs field -- Obama is no longer able to move through the room quickly. He is far slower than the relatively unknown Dutch Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende, a much lighter particle in this metaphor.

Genius Unrecognised

The question the scientists at CERN are hoping to answer is whether or not the Higgs particle is really at work in the physical world. In other words, if it actually exists or not.

It is "somewhat ironic," says Higgs, that his article was first rejected by Physics Letters, a journal published at the same CERN, in 1964. "It was only much later that my roommate at university in Edinburgh told me the editor had not understood it at all," he recalls. The editor replied that he "did not see the relevance of the work for physics" and wrote a polite letter suggesting he send his article to another magazine, like Nuovo Cimento.

"It was only later that I discovered that that suggestion was not so polite after all," Higgs recalls, "since Nuovo Cimento publishes all articles without peer review" -- in other words, regardless of their quality.

Higgs had gone another route by then. He had added a paragraph to the article demonstrating his "new" mechanism would be able to produce particles with proper mass. "But I was thinking in the wrong direction," Higgs adds. "I thought of hadrons." Hadrons, which are subject to the strong force, one of the four elementary forces in nature, were a hot topic among scientists at the time.

Still, it was that extra paragraph, Higgs suspects, that led to his article being accepted by the American scientific journal Physical Review Letters, and, more importantly, that drew attention to it.

The Shoulders of Giants

At a speech given to colleagues last Friday at NIKHEF, Higgs credited the scientists who paved the way for him and who dotted the i's and crossed the t's of his work. He thanked countless people, including a number of Nobel Prize winners. Among the latter were people like Yoichiro Nambu, who got the idea for spontaneous broken symmetry from superconductor research into particle physics. Or Phil Anderson, who came close, but never drew the same final conclusions that Higgs did. Or Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, who unified the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces under the Standard Model. And the Dutch scientists Gerard 't Hooft and Martin Veltman, who gave this electroweak force a sturdy theoretical foundation.

It was with the electroweak force that the Higgs mechanism proved particularly useful. This theory covers the interaction between weightless particles (the photons of the electroweak force) and massive particles (like the W- and Z-particles of the weak nuclear force). Only Higgs' mechanism could explain the asymmetrical masses, through the existence of a particle which came to be known as the Higgs particle, or Higgs boson, since a well-attended congress in 1972.

Over the years, physicists became convinced the Higgs particle might actually be detectable. Indirectly, through precise measurements of the electroweak force at CERN and Fermilab in the United States, they established how. "And that is when my life as a boson really started," Higgs says.

It could have been different. When Higgs' manuscript arrived at Physical Review Letters on Aug. 31, 1964, the magazine had just published an article by the Belgian physicists Francois Englert and Robert Brout. They had come to the same conclusion through different means. "Because their method was quite complicated they were somewhat uncertain of their results. Perhaps that is why they did not tout the applications it might have in particle physics," Higgs says carefully.

This may be true, but the "Englert field" never gained popular recognition, and neither did the Brout boson. And this is despite the fact that his name only has five letters, as Brout is said to have remarked somewhat wryly. And even Higgs' painstaking efforts to pay tribute to his fellow researchers can do little to change the fact that it is his name that is now forever associated with the elusive boson.

What If It Doesn't Exist?

But what if the Higgs particle isn't found? "Then I no longer understand a whole area of physics which puzzled me as an undergraduate," Higgs answers, sounding determined. "And I thought the one thing we understand rather well now is the electromagnetic interaction and how it relates to electroweak theory."

Isn't it strange to see billions being invested in

pursuit of a particle bearing his own name? "If

physicists were looking for a different particle they

would have constructed an accelerator just as strong and

experiments just as complex," Higgs says with a

shrug.

Lessons from Bt

Cotton

ISIS Letter to Hilary Benn, UK Secretary of State for the Environment

Rt Hon Hilary Benn MP, Secretary of State for the

Environment, DEFRA

4 January 2009

Dear Mr. Benn,

I am writing to you onbehalf of the Institute of Science in Society (ISIS), a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to providing critical and accessible scientific information to the public and to promoting accountability and sustainability in science.

As director of ISIS and a member on the Roster of Experts of the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, I have been involved in monitoring scientific developments of genetic modification especially in relation to risk assessments on genetically modified organisms.

I understand that you are particularly keen to promote GM crops for developing countries, perhaps on account of the bad advice and misinformation you have received, especially on the supposed 'success' of Bt cotton in India, which I have recently heard described by invited speakers at the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee meeting.

My colleagues and I have been following the developments of Bt cotton in India since the beginning, and I was motivated to get to the bottom of the debate over the role that Bt cotton has played in exacerbating farmer suicides in India, which has raised grave concerns worldwide.

The results of my investigations are summed up in the two reports enclosed: Farmer Suicides and Bt Cotton Nightmare Unfolding in India (http://www.i-sis.org.uk/farmersSuicidesBtCottonIndia.php), and Mealy Bug Plagues Bt Cotton in India and Pakistan (http://www.i-sis.org.uk/mealybugPlaguesBtCotton.php). Together, these reports show that Bt cotton has indeed exacerbated farmer suicides in India by increasing their indebtedness. In addition, Bt cotton is creating an ecological disaster in secondary and new pests, resistant pests, new diseases, and above all, soils so depleted in nutrients and beneficial microorganisms that they would cease to support the growth of any crop in a decade.

I have submitted both reports to the Environment Minister of India and urged him to do his utmost to stop Bt cotton and any further GM crops in India.There are also serious health concerns over GM crops in general which more and more scientists are now acknowledging since I pointed them out in my book, Genetic Engineering Dream or Nightmare (http://www.i-sis.org.uk/genet.php) first published in 1997/8.

More importantly, there is a developing scientific consensus that organically managed non-GM agriculture and localised food systems is the way ahead for us all, developed and developing countries. It not only provides a lifeline for farmers caught in the GM trap, but also guarantees food security while mitigating climate change.

Your sincerely,

Director

Institute of Science in Society