| THE HANDSTAND | FEBRUARY-MARCH2010 |

OPEN YOUR HISTORY BOOKS

| Yemen - The Return Of

Old Ghosts By Adam Curtis January 15, 2010 "BBC" -- Friday, 8 January 2010 -- What I find so fascinating about the reporting of the War on Terror is the way almost all of it ignores history - as if it is a conflict happening outside time. The Yemen is a case in point. In the wake of the underpants bomber we have been deluged by a wave of terror journalism about this dark mediaeval country that harbours incomprehensible fanatics who want to destroy the west. None of it has explained that only forty years ago the British government fought a vicious secret war in the Yemen against republican revolutionaries who used terror, including bombing airliners. But the moment you start looking into that war you find out all sorts of extraordinary things. First that the chaos that has engulfed the Yemen today and is breeding new terrorist threats against the west is a direct result of that conflict of forty years ago. Secondly it also had a powerful and corrupting effect on Britain itself. To fight the war both Conservative and Labour governments in the 1960s set up international arms deals with the Saudis. These involved bribery on a huge scale which led to the Al Yamamah scandal that still festers today. To fight the war in secret the British government also allowed the creation of a private mercenary force. Out of it would come today's privatized military industry that fights wars for dictators throughout Africa and is deeply involved in fighting against the insurgency in Iraq. The key figure behind Britain's involvement was called Colonel David Stirling. He brought Britain into the war, created the mercenary amy, and set up the Saudi Arms deal. Stirling was one of the main characters in a documentary series I made called The Mayfair Set, and a large part of the first episode tells the inside story of Britain's role in the Yemen war in the 1960s. I thought I would put up that section plus a brief background to our whole involvement in Yemen. Here is a map of Aden in the 1960s:

And here is one of the Yemen:

By the mid 60s the revolt had developed into a bitter and vicious insurgency as the NLF used terror against British civilians as well as attacking the soldiers. Here is some footage shot by the BBC Panorama programme of the aftermath of the killing of a British Civil Servant on a dusty road just outside the Crater district of Aden. As well as showing the details it also conveys the mood of a once confident imperial power caught up in something it doesn't fully understand and feeling its power slipping away. It is also interesting how back then Panorama broadcast shots that lingered far longer on the dead body than we would be allowed to today. As the insurgency continued both sides turned to terror. An Amnesty report in 1966 alleged that the British were torturing prisoners including beating them and burning them with cigarettes. The British soldiers were also stripping the Arab prisoners naked to humiliate them. Here is a short piece of film that was grabbed by a Reuters cameraman in 1967. It graphically shows the hatred of the local people that had built up in the British troops. The terrorists meanwhile had resorted to throwing grenades into childrens' parties and had blown up a DC3 civilian airliner over the Yemen killing everyone on board. Here is a news item where a BBC journalist shows some of the Improvised Explosive Devices that were being used against civilians. At the same time as the insurgency began in the south, in Aden, another revolution happened in the North Yemen. A group of republicans who were also followers of President Nasser overthrew the ruling royal family. Nasser then sent Egyptian troops to support the republicans. Many in the British government wanted to recognise the new regime, but a small group in the security services, led by David Stirling, persuaded the Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan, to let them organise a covert war in the deserts and mountains of Yemen in support of the royal family. These men had a romantic and simplified view of the world. They did not see this war as a nationalist struggle but as part of a much wider fight against a communist takeover of the world. Engaging in this global conflict would be a way of recapturing Britain's power and greatness. Stirling also believed that selling arms and planes to the Saudis would not only help fight the war, but would also re-establish Britain's influence in the Middle East in a new way - through the arms trade. And he was right. Although the mecenaries failed to restore the royalists in Yemen, they did help defeat Nasser and destroy his anti-colonial project. But more than that, their secret war also helped re-establish western influence in the Arab world in a new way. In a post-imperial age the British returned to the Middle East by supporting and propping up regimes through selling arms and through mercenary armies. Just as Stirling had intended. But it had a terrible price. The regimes that Britain, and America, would support for the next forty years were mostly corrupt and despotic. The very regimes that Nasser had told the Arab world were a part of the past which the modern world would sweep away. The man who foresaw this was the British Prime Minister - Harold MacMillan. In 1963 he wrote privately: "It is repugnant to political equity and prudence alike that we should so often appear to be supporting out-of-date and despotic regimes and to be opposing the growth of modern and more democratic forms of government." The Islamism that we face today rose up in the 1970s precisely as a reaction to those corrupt regimes and their western backers. It too is an anti-colonial project that is very similar to Nasser's vision of a united Arab world free of western influence - but with religion bolted on. And now, to fight it, we are preparing to send arms and "intelligence advisers" to help prop up a corrupt regime in Yemen. To the Arabs in Yemen it must seem like deja vu. We are the old ghosts who have returned. Here is the section from The Mayfair Set. It begins with the owner of the Clermont Club in Mayfair, John Aspinall, musing on the group of entrepreneurs and adventurers who spent their time gambling in his club. Men like David Stirling. |

Frankincense trees can grow for 300 years

By ALAN BURDICK Published: March 25, 2007

The road to the forest of frankincense trees, on the Yemeni island of Socotra, is a rough one. From the passenger seat of a battered Toyota Land Cruiser, it looked like pure rock pile, on and on, up, down, over. Ahmed Said, my driver and guide, wrestled the wheel like a man engaged, surely and calmly, in a struggle to the death. When at last, after 90 minutes, he stopped and got out, we had traveled perhaps no more than five miles.

We stood on a rise overlooking a riverbed rushing with water. The ground underfoot was a rubble of granite boulders and chunks of sharp limestone karst. Small trees — short and gnarled, resembling mesquite — surrounded us. Ahmed approached one and pointed to an amber drop of sap oozing from its trunk: the essence of frankincense. Until that moment I’d had no clear idea what exactly frankincense was; nor that it derives from the sap of a tree; nor that, as Ahmed explained, Socotra is home to nine species of the tree, all unique to the island. I caught the drop of sap on my finger and inhaled a sharp, sweet fragrance; then I put it to my tongue. The torture of the drive was forgotten, and for the briefest moment, under the hot Yemeni sun, I tasted Christmas.

Situated 250 miles off the coast of Yemen, Socotra is the largest member of an archipelago of the same name, a four-island ellipsis that trails off the Horn of Africa into the Gulf of Aden. A mix of ancient granite massifs, limestone cliffs and red sandstone plateaus, the island brings to mind the tablelands of Arizona, if Arizona were no bigger than New York’s Long Island and surrounded by a sparkling turquoise sea.

Some 250 million years or more ago, when all the planet’s major landmasses were joined and most major life-forms were just a gleam in some evolutionary eye, Socotra already stood as an island apart. Ever since, it has been gathering birds, seeds and insects off the winds and cultivating one of the world’s most unusual collections of organisms. In addition to frankincense, Socotra is home to myrrh trees and several rare birds. Its marine life is a unique hybrid of species from the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean and the western Pacific. In the 1990s, a team of United Nations biologists conducted a survey of the archipelago’s flora and fauna. They counted nearly 700 endemic species, found nowhere else on earth; only Hawaii and the Galapagos Islands have more impressive numbers.

Lately Socotra has begun to attract a new and entirely foreign species — tourists. A modest airport went up in 1999. (Before then, the island could be reached only by cargo ship; from May to September, when monsoon winds whip up the sea, it could be cut off entirely.) That year, 140 travelers visited. The annual figure now exceeds 2,500: a paltry number compared with, say, the Galapagos, but on an island with only four hotels, two gas stations and a handful of flush toilets, it’s a veritable flood.

They — I should say “we” — constitute an experiment. Encouraged by a United Nations development plan, Socotra has opted to avoid mass tourism: no beachfront resorts; instead, small, locally owned hotels and beachfront campsites. The prize is that rarest of tourists, eco-tourists: those who know the little known and reach the hard to reach, who will come eager to see the Socotra warbler, the loggerhead turtle, the dragon’s blood tree — anything, please, but their own reflection.

Riding with Ahmed, it was immediately evident that, though the island is small in size, it cannot possibly be seen without a hired driver and guide, for the simple reason that there are few proper roads, fewer road signs and no road maps.

The first paved roads were built by the Yemeni government only two years ago: wide, open scabs on the landscape that stretch across the island yet see virtually no traffic. The new roads, it turned out, were a sore spot with Ahmed and the United Nations Socotra Archipelago Conservation and Development Programme. “The experience is so different if you spend 45 minutes on a road versus three or four hours,” Paul Scholte, the program’s technical adviser in Sana, Yemen’s capital, said to me. “The whole perception of the island changes due to the road.” Then there was the matter of placement. Only at the last minute did the S.C.D.P. manage to convince the government not to send the road through a stretch of coastline designated as a nature preserve. It’s fair to say that Socotra’s future may be read in the lines of its roads: how many, how wide, where they lead and who is encouraged to travel on them.

Ahmed took me to the beach that would have been paved over: shimmering blue water, powdery white sand and not a soul in sight. A ghost crab, pure white, with just its pin-stalk eyes peeking above the water like twin periscopes, drifted by on a current in the shallows. I watched it watch me and then bury itself in the sandy floor.

In devising its eco-tourism plans, Socotra aims to follow in the footsteps of the Galapagos. Unlike the Galapagos, however, Socotra is significantly inhabited, and has been for some 2,000 years. More than 40,000 people now live there: many in Hadibu, the island’s main town, the rest scattered in small stone villages, working as fishermen and semi-nomadic Bedouin herders. Nature and culture are longstanding neighbors.

Late one afternoon Ahmed and I drove to a Bedouin village high on the plateau, where we would stay the night. Just before sundown, we arrived at a small cluster of low-ceilinged stone structures, home to an extended family and their herd of goats. After removing our shoes and entering, we were given the best pillows to recline on and served tea. Dinner followed: goat’s-milk yogurt, drunk from a communal bowl; a thin, freshly baked flatbread; and a large plate of rice cooked in goat’s milk, which we ate with the fingers of our right hands.

Ahmed led the conversation, which involved goats and water projects. It proceeded not in Arabic but in Socotri, a language that is unique to the island and related to some of the oldest of the Near East. Socotri describes 24 months in its calendar, each roughly 13 days long, including the Month of the Cow’s Breath, when heavy winds turn the sea to foam, and the Month of Crabs, when ghost crabs crowd the beaches by the thousands. By the light of a kerosene lamp I cajoled our host into teaching me several Socotri phrases. The most handy was the one for “I’m full.” No, thank you, no more goat’s milk, goat’s-milk yogurt or fricasseed goat, I’m full — kheapaak!

Blankets and mats were offered to sleep on. But mosquitoes, born from a nearby rainwater tank, had found me, so I stepped outside and set up my tent. The sky was thick with stars. Lying on the rocky ground, with the scent of frankincense fresh in memory, I felt as though I had stumbled into a chapter of the Old Testament. Well before dawn I woke to the sound of the family patriarch’s voice warbling a long, mournful prayer. He finished after a few minutes, and the night closed over the sound. I listened awhile longer to the holy darkness, then fell again to sleep.

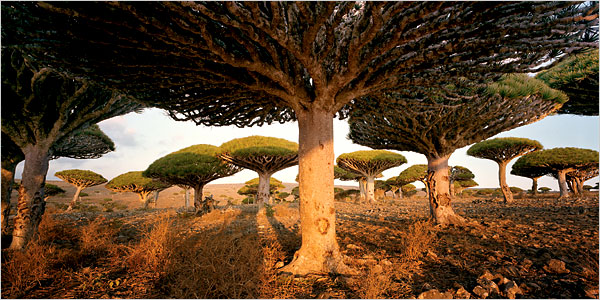

The next morning we made for the forest of dragon’s blood trees. The dragon’s blood tree, Dracaena cinnabari, is Socotra’s flagship species. With a vertical trunk and arching canopy, the tree resembles a parasol that’s been blown inside out. When its trunk is cut, it oozes a red sap that gives rise to cinnabar, a resin with famous medicinal qualities. We had seen the trees scattered here and there on the plateau, but the highest concentration was in a nature reserve tucked high in the Haghier Mountains. We would drive to the base of the range and hike in.

On the drive up, Ahmed stopped to chat with a Bedouin man herding cattle with his young son. Through the open window, he and Ahmed gently pressed their foreheads and noses together, the customary greeting among men on Socotra. For the equivalent of $10, the man agreed to be our foot guide. He hopped into the back seat and left his son, who looked no older than 7, to tend the cattle.

The Haghiers are the original, uplifted core of the island, all worn and crumbling granite. Our path led upward invisibly from boulder to boulder, through low shrubs and aloes and amid the omnipresent droppings of goats and cattle. The United Nations conservation plan in 2000 divided Socotra into usage zones; more than 70 percent of the island is national park, off limits to development. Even here, though, livestock grazing is permitted, and well into the distance I could see stone walls marking tribal grazing ranges. I wondered aloud at what stage the conservation plan would begin to restrict the livestock.

“We have to be careful with the local communities,” Ahmed said. “We can’t just say, ‘Stop, stop, stop.’ They need to see a benefit first.” Our $10 guide, I understood, was one step in the education process.

After two hours we reached the peaks, a couple thousand feet up. I could see the coast below and the outline of Hadibu pressed against it. Ahmed handed me his binoculars and pointed a few yards away to a bird foraging on the ground: the Socotra bunting, with a rosy breast and black-and-white striped head. It is among the rarest of the island’s endemic species and is threatened by predation from feral, non-native cats.

The forest of dragon’s blood trees, when we at last reached it, did not much resemble a forest, at least not the dense, dark sort associated with giant reptiles of myth. It was open and sparse, as though a light rain of broken umbrellas had fallen on the hillside. Recent years have seen a troubling decline in the tree’s numbers. Although many older examples are present on the island (they can grow for 300 years or more), the younger generation is all but absent, with saplings found growing only on cliff sides and in the most inaccessible highlands. The entire species may well be headed for extinction.

Scientists are unsure why. Grazing could be one cause; as development projects have brought a more steady supply of water to Bedouin villages, the herds of livestock have grown larger and more stable. A more important factor may be climate change: the island has seen a reduction in cloud and mist cover, which may affect the ability of dragon’s blood seeds to germinate.