"Australian

Aboriginal Art, Copyright Law and the Australian

Courts - an example of the flexible management of

difference?"

Martin Hardie, Florida State University, Panama

City, Republic of Panama.

Conference: Born of Desertion: Singularity, Collectivity,

Revolution - March 20-22 at the University of Florida,

Gainesville, USA.

Presented by Center for the Humanities and Public Sphere,

the Department of English, and the Marxist Reading Group.

This presentation seeks to give an outline of the facts

involving the challenges posed by Australia Aboriginal

art and indigenous concepts of ownership to the law of

Copyright in Australia. The draft paper upon which the

presentation is based can be found at:

http://mailer.fsu.edu/~mhardie/wandjuk.html.

In the cases examined in the paper we see the courts

undergo a passage from the perceived exclusion of

Aboriginal artists from the protection of the law to one

were they are capable of seeking remedies under both the

existing Copyright regime and the ancient principles of

doing equity.

After many years of the existence of a perceived wisdom

to the effect that Aboriginal art was not capable of

protection by copyright law it was in the final case of

the series examined (Bulun Bulun v R & T Textiles Pty

Ltd) that the Federal Court of Australia cleared away any

obstacles and created a precedent for courts to intervene

to protect Aboriginal ritual knowledge from exploitation

that is contrary to the particular law and custom shown

to exist in any one case. In doing so the court

recognised a separate and distinct right to the right

subsisting in an artistic work of a copyright owner based

upon the ancient principles of doing "equity".

Prior to this series of cases Aboriginal art was

originally perceived as not being subject to the law of

copyright because of the "traditional" nature

of its designs - simply it was argued they were regarded

as not capable of being "original" within the

meaning of the relevant law. The approach taken by the

Federal Court in Bulun Bulun allows for both communal

interests and copyright interests to be litigated.

Nevertheless their continues in some quarters a call for

legislative intervention in order that all members of

Aboriginal communities, wherever they are situated and

whatever their custom could enforce a general legal

right. I argue that this general approach misunderstands

the importance of the case by case (differential

approach) adopted by the Federal Court in the Bulun Bulun

case. It is arguable that a legislative response would

entail a law that would treat all the subjects of the

proposed law (Aboriginal artists) generally and according

to the overarching applicable law. It would call for a

static definition of what is Aboriginal

"tradition" applicable to interchangeable

particulars.

It may be the Federal Court's approach is an example of

the flexible management of difference whereby it repeats

in different cases its role to do equity between the

parties. Not only do I argue that the approach is

sensible and just, taking account of difference as it

does, it may be an example of conduct concerning

"non-exchangeable and non-substitutable

singularities". In short the Federal Court may

repeat the Bulun Bulun case in other circumstances - that

is it may "behave in a certain manner, but in

relation to something unique or singular which has no

equal or equivalent."

'

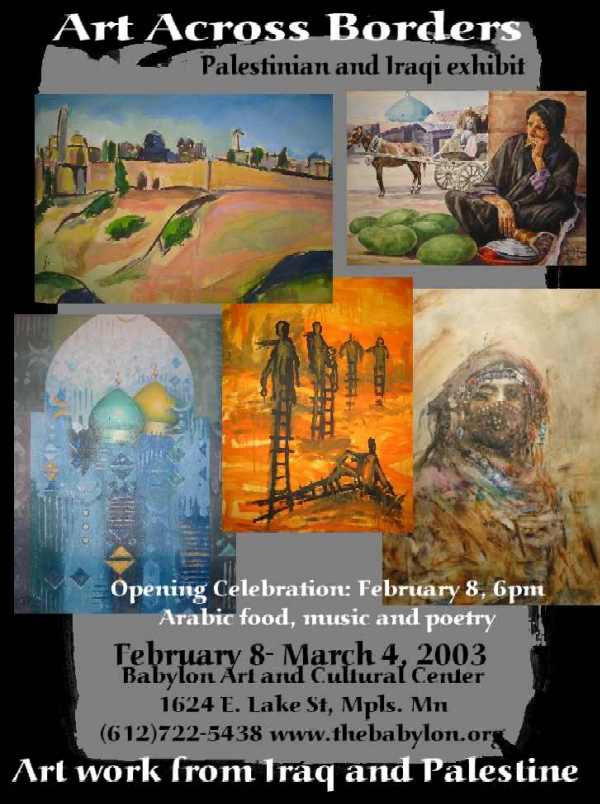

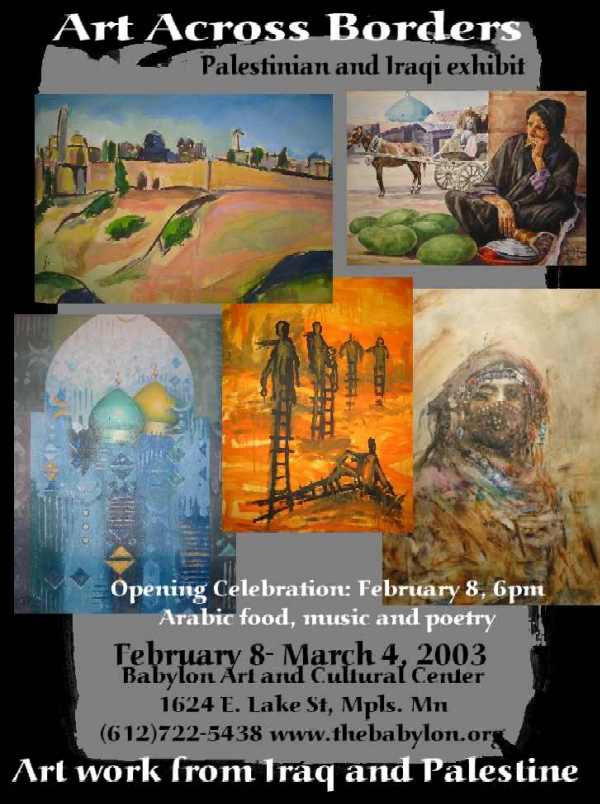

“Art

Across Borders”

Mission

Statement/Iraqi-Palestinian Exhibit

It is our

belief that art is a powerful means of raising

cross-cultural awareness, creating a dialogue between

peoples that have been caught in a long history of

misconceptions about one another, and of providing a

human face to peoples that have been largely vilified.

It is based on this belief that

we have organized “Art Across Borders,” a

traveling exhibition of artwork from artists who are

currently living in Iraq and Palestine. Organizers

of this project spent ten days in Iraq and over a month

in Palestine this summer. There we worked and

lived side by side with artists in these countries,

people that are facing incredible odds against their very

survival yet continue to find the ability to create.

In Iraq, organizers met with around

20 artists, including two pioneers of the modern Iraqi

art movement, Mohammed Ghani and Noori Al-Rawi. Organizers

conducted video interviews with artists in Iraq, which

have been made into a short documentary. This

documentary will be included with the more than forty

Iraqi artworks that will be included with this exhibit.

These

works reflect an unparalleled diversity of styles and

subject matter, from traditional Arabic calligraphy, to

the experiments with symbols and texture of modern

painter Shaddad, who focuses on relations between men and

women in his works. The history of over six

thousand years of civilization is evident in the

paintings of these artists, as well as the development of

a modern society that knows it has been cut off from the

rest of the world.

During our six-week journey

to Palestine, we were able to see first hand the

disruption the current occupation creates in daily life.

Simple tasks such as buying groceries for your family, or

taking your children to school often become life-risking

endeavors. In the midst of this violence and

upheaval, the artists we met bravely continue to use

their art as a way to provide hope and inspiration to

themselves and their people.

Although the Palestinian

people and the artists in their society have continually

been made refugees, from the Al-Nakba of 1948 to the

latest Israeli land grab and settlements of today, these

artists continue to search for a sense of home and

permanency through their art. An example of this

is the work of Mohammed Abu-Sall one of the emerging

talents from the Gaza Breij refugee camp in the Gaza

Strip, which celebrates the cactus as a symbol of the

tenacity and resistance of the Palestinian people.

The more than thirty

Palestinian works that will be exhibited reflect the

strength of a people who have survived more than fifty

years of occupation. Through displaying these

varied works, we will challenge the viewer to see

Palestinians as individual human beings, as creators of

beauty, as people not so different from us. Already, the

people of Palestine feel that they have been forgotten or

at least forsaken by the International community. Through

the artwork that we have been honored to carry from

Palestine, so too do we carry the hope and strength of

the Palestinian people -that they may not be forgotten.

Our goal with this exhibit,

first and foremost, is to provide an opportunity for

Iraqi and Palestinian artists to speak in their own

voices about the conditions in their countries. Through

their art, these artists reflect the greater humanity of

countries who’s individuality and rich cultures have

been drowned in a sea of political maneuvering. We

hope that this exposure of the world audience to these

art works will reassert the place of Iraqis and

Palestinians in the world’s conscience.

Secondly,

we hope to exhibit these works to the widest possible

audience, and to use this as a way to create a dialogue

about the conditions these works reflect. We invite

you to join with us in this process of opening doors to a

discussion that will elevate our own understanding of our

place in the world, and the commonality and vitality of

the human existence, no matter where a person happens to

live.

Lastly,

we see this exhibit as a beginning rather than a final

product. We intend to continue this exchange with

Iraqi and Palestinian artists, with the next Art Across

Borders trip to the Middle East slated for spring/summer

of 2003. We are also considering other projects,

such as a continually bringing art journals and supplies

to artists in Iraq, organizing a joint U.S./Iraqi show in

Baghdad (organizers received invitations from three

different galleries), and further collaborative projects

such as murals and workshops. Through this

continual exchange of ideas, technique and work, we hope

to foster a person to person, artist to artist dialogue

that weakens the dangerous and destructive divisions that

are being drawn throughout the world by forces greater

than the average human being.

If you

are interested in getting involved in this project, or

organizing a showing of the exhibition in your area,

please contact Meg Novak at (612) 722-5438, or

megbabylon@hotmail.com.

The

MARTYR GHASSAN KANAFANI CULTURAL FOUNDATION (Martyr

Ghassan Kanafani was assassinated by the Israeli Moussad

in Beirut on July 8,1972) had published a book entitled:

Like Roses in the

Wind; Self Portraits and

Thoughts

The Introduction of the book says: During the summer of

2000, we decided to work on a self-portrait project

with children aged 5 to 6 and a small group of older,

mentally disabled children. The subject, both

educationally and artistically, is not new, but

nevertheless of great visual, psychological and

emotional importance because it deals with identity. The

main aim of the project was for the children to express,

visually and verbally, their self perception and their

perception of, and identification with, the world they

live in and interacts with.

The children participating in this project all attend The

Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Foundation's kindergartens in

six different Palestinian refugee camps, suburban and

rural areas in Lebanon. They are fourth generation

Palestinian refugees and descendants of the Palestinians

who were expelled from Palestine to Lebanon during the

Nakba ( the catastrophe) in 1948 as a result of the

establishment of Israel (The Zionist State). their status

remains as refugees up till today.

The book was coordinated and edited by Laila Ghassan

Kanafani.

All proceeds from the sale of this book will go to

support Ghassan Kanafani cultural Foundation.

P.O.BOX: 13-5375 Beirut - Lebanon

E- mail: gkcf@cyberia.net.lb

Kandahar'

offers glimpse of Afghanistan's terrible beauty

By CLAIRE DUQUETTE

The Daily Press

Friday, January 24th, 2003

"Kandahar" opens and closes with the image of a

solar eclipse, the blotting out of life-giving sun that

is both beautiful and dangerous to look upon. So it is

with the Afghanistan of Mohsen Makhmalbaf's film, which

takes us into a pre-9/11 journey into a country torn by

years of war and oppressed under strict Taliban rule.

The film tells the story of Nafas, an Afghan expatriot

living in Canada who returns to her native land to find

and rescue her sister, who has told Nafas she plans to

commit suicide during the final eclipse of the 20th

century. Nafas, a journalist, undertakes the perilous

trip to Kandahar, unsure of how to find her sister, but

determined to save her and restore her hope.

Nafas, a journalist records her trip on a black tape

recorder - her "black box" as she calls it,

relaying her hopes and her horror at all she finds.

Smuggled into Afghanistan by way of an Iranian refugee

camp posing as the fourth wife of an Afghan man, Nafas

soon finds herself robbed and heading to Kandahar with

only the guidance of a school-age boy.

Throughout the short, desperate journey she is made

keenly aware of the oppression of women, the absurdities

of trying to obtain medical care, and the shock of

encountering a camp of men maimed by landmines, an

ever-present danger.

She is aided in her journey by an American who came to

Afghanistan "to find God" but has found only a

suffering people he helps by supplying rudimentary

medical care, and by an local con man, who hides under a

burqa to help Nafas journey to Kandahar mixed in with a

wedding party.

Although the film is shot to resemble a documentary, it

is filled with beautiful landscapes and surreal imagery.

The opening sequence offers a vision of figures scurrying

across the desert sand the is reminiscent of the

computerized army in a 'Star Wars' film. But this army's

peculiar gait is the result of being a one-legged troupe

racing across the sand in a desperate attempt to be the

first to reach sets of artificial limbs dropping from the

sky - parachuted in by the Red Cross.

The legs themselves, drifting lazily through the sky

could have come from a painting by Magritte or Dali,

limbs cut off from all other reality.

Indeed, this is a world full of cruel cuts. The people

are cut from their limbs. Girls are cut off from

education, and women are cut off from the world by

religious dogma and the ever-present burqa.

There is no neat or happy ending in "Kandahar"

just as there is still no neat or happy ending for the

people living in Afghanistan. Just a terrible beauty and

determination to survive.

|