| the

united

nations is already under

international censure, what trust can we put in the

security council now ?? There follow

excerpts from the following article::

Economic Sanctions as a

Weapon of Mass Destruction Weapon of Mass Destruction

by Joy Gordon

Harpers Magazine November 2002

If any international act in the last decade is sure to

generate enduring bitterness toward the United States, it

is the epidemic suffering needlessly visited on Iraqis

via U.S. fiat inside the United Nations Security

Council. . Invoking security concerns including those not

corroborated by U.N. weapons inspectors U.S.

policymakers have effectively turned a program of

international governance into a legitimized act of mass

slaughter.

The U.N. adopted economic sanctions in 1945, in its

charter, as a means of maintaining global order, it has

used them fourteen times (twelve times since 1990). But

only those sanctions imposed on Iraq have been

comprehensive, meaning that virtually every aspect of the

country's imports and exports is controlled.

How was the danger of goods entering Iraq assessed, and

how was it weighed, if at all, against the mounting

collateral damage? All U.N. records that could answer my

questions are kept from public scrutiny.

The operation of Iraq sanctions involves numerous

agencies within the United Nations. The Security

Council's 661 Committee is generally responsible

for both enforcing the sanctions and granting

humanitarian exemptions. The Office of Iraq Programme

(OIP), within the U.N. Secretariat, operates the Oil for

Food Programme. Humanitarian agencies such as UNICEF and

the World Health Organization work in Iraq to monitor and

improve the population's welfare, periodically reporting

their findings to the 661 Committee. The United

States has fought aggressively

throughout the last decade to purposefully minimize the

humanitarian goods that enter the country. And it has

done so in the face of enormous human suffering,

including massive increases in child mortality and

widespread epidemics. Iraq was allowed to purchase a

sewage-treatment plant but was blocked from buying the

generator necessary to run it; this in a country that has

been pouring 300,000 tons of raw sewage daily into its

rivers.

IRAN BEFORE THE GULF WAR

Saddam Hussein's government is well known for its

human-rights abuses against the Kurds and Shi'ites, and

for its invasion of Kuwait. What is less well known is

that this same government had also invested heavily in

health, education, and social programs for two decades

prior to the Persian Gulf War. While the treatment of

ethnic minorities and political enemies has been

abominable under Hussein, it is also the case that the

well-being of the society at large improved dramatically.

The social programs and economic development continued,

and expanded, even during Iraq's grueling and costly war

with Iran from 1980 to 1988, a war that Saddam Hussein

might not have survived without substantial U.S. backing.

Before the Persian Gulf War, Iraq was a rapidly

developing country, with free education, ample

electricity, modernized agriculture, and a robust middle

class. According to the World Health Organization, 93

percent of the population had access to health care.

Ninety-five percent of the population had access to

potable water.

POST GULF WAR : SANCTIONS

A USA Defense Department evaluation noted that

"Degraded medical conditions in Iraq are primarily

attributable to the breakdown of public services (water

purification and distribution, preventive medicine, water

disposal, health-care services, electricity, and

transportation). . . . Hospital care is degraded by lack

of running water and electricity."

Nearly everything for Iraq's entire infrastructure

electricity, roads, telephones, water treatment as

well as much of the equipment and supplies related to

food and medicine has been subject to Security Council

review. In practice, this has meant that the United

States and Britain subjected hundreds of contracts to

elaborate scrutiny, without the involvement of any other

country on the council; and after that scrutiny, the

United States, only occasionally seconded by Britain,

consistently blocked or delayed hundreds of humanitarian

contracts.

In response to U.S. demands, the U.N. worked with

suppliers to provide the United States with detailed

information about the goods and how they would be

used, and repeatedly expanded its monitoring system,

tracking each item from contracting through delivery and

installation, ensuring that the imports are used for

legitimate civilian purposes. Despite all these measures,

U.S. holds actually increased. In September 2001 nearly

one third of water and sanitation and one quarter of

electricity and educational - supply contracts were on

hold. Between the springs of 2000 and 2002, for example,

holds on humanitarian goods tripled.

Although most contracts for food in the last few years

bypassed the Security Council altogether, political

interference with related contracts still occurred. A

Syrian company asked the committee to approve a contract

to mill flour for Iraq. Whereas Iraq ordinarily purchased

food directly, in this case it was growing wheat but did

not have adequate facilities to produce flour. The

Russian delegate argued that, in light of the report the

committee had received from the UNICEF official, and the

fact that flour was an essential element of the Iraqi

diet, the committee had no choice but to approve the

request on humanitarian grounds. The delegate from

China agreed, as did those from France and Argentina. But

the U.S. representative, Eugene Young, argued that

"there should be no hurry" to move on this

request: the flour requirement under Security Council

Resolution 986 had been met, he said; the number of holds

on contracts for milling equipment was "relatively

low"; and the committee should wait for the results

of a study being conducted by the World Food Programme

first. The British delegate stalled as well, saying that

he would need to see "how the request would fit into

the Iraqi food programme," and that there were still

questions about transport and insurance. In the end,

despite the extreme malnutrition of which the committee

was aware, the U.S. delegate insisted it would be

"premature" to grant the request for flour

production, and the U.K. representative joined him,

blocking the project from going forward.

Many members

of the Security Council have been sharply critical of

these practices. In an April 20, 2000, meeting of the

661 Committee, one member after another challenged the

legitimacy of the U.S. decisions to impede the

humanitarian contracts. The problem had reached "a

critical point," said the Russian delegate; the

number of holds was "excessive," said the

Canadian representative; the Tunisian delegate expressed

concern over the scale of the holds. The British and

American delegates justified their position on the

grounds that the items on hold were "dual use"

goods that should be monitored, and that they could not

approve them without getting detailed technical

information. The French delegate suggested, that

providing prompt, detailed technical information was not

sufficient to get holds released: a French contract for

the supply of ventilators for intensive care units

had been on hold for more than five months, despite his

government's prompt and detailed response to a request

for additional technical information and the obvious

humanitarian character of the goods. Many members

of the Security Council have been sharply critical of

these practices. In an April 20, 2000, meeting of the

661 Committee, one member after another challenged the

legitimacy of the U.S. decisions to impede the

humanitarian contracts. The problem had reached "a

critical point," said the Russian delegate; the

number of holds was "excessive," said the

Canadian representative; the Tunisian delegate expressed

concern over the scale of the holds. The British and

American delegates justified their position on the

grounds that the items on hold were "dual use"

goods that should be monitored, and that they could not

approve them without getting detailed technical

information. The French delegate suggested, that

providing prompt, detailed technical information was not

sufficient to get holds released: a French contract for

the supply of ventilators for intensive care units

had been on hold for more than five months, despite his

government's prompt and detailed response to a request

for additional technical information and the obvious

humanitarian character of the goods.

CLEAN WATER, PURIFICATION:

"Dual-use" goods, of course, are the ostensible

target of sanctions. Also under suspicion is much of the

equipment needed to provide clean water. Chlorine, for

example vital for water purification, and feared as a

possible source of the chlorine gas used in chemical

weapons is aggressively monitored, and deliveries have

been regular. Every single canister is tracked from the

time of contracting through arrival, installation, and

disposal of the empty canister.

Last year the United States blocked contracts for

water tankers, on the grounds that they might be used to

haul chemical weapons instead. Yet the arms experts at

UNMOVIC* had no objection to them: water tankers with

that particular type of lining, they maintained, were not

on the "1051 list" the List of goods that

require notice to U.N. weapons inspectors. Still, the

United States insisted on blocking the water

tankers this during a time when the major cause of

child deaths was lack of access to clean drinking water,

and when the country was in the midst of a drought.

Among the many deprivations Iraq

has experienced, none is so closely correlated with

deaths as its damaged water system. Prior to 1990, 95

percent of urban households in Iraq had access to potable

water, as did three quarters of rural households. Soon

after the Persian Gulf War, there were widespread

outbreaks of cholera and typhoid diseases that had

been largely eradicated in Iraq as well as massive

increases in child and infant dysentery, and skyrocketing

child and infant mortality rates. By 1996 all

sewage-treatment plants had broken down. As the state's

economy collapsed, salaries to state employees stopped,

or were paid in Iraqi currency rendered nearly worthless

by inflation. Between 1990 and 1996 more than half of the

employees involved in water and sanitation left their

jobs. Among the many deprivations Iraq

has experienced, none is so closely correlated with

deaths as its damaged water system. Prior to 1990, 95

percent of urban households in Iraq had access to potable

water, as did three quarters of rural households. Soon

after the Persian Gulf War, there were widespread

outbreaks of cholera and typhoid diseases that had

been largely eradicated in Iraq as well as massive

increases in child and infant dysentery, and skyrocketing

child and infant mortality rates. By 1996 all

sewage-treatment plants had broken down. As the state's

economy collapsed, salaries to state employees stopped,

or were paid in Iraqi currency rendered nearly worthless

by inflation. Between 1990 and 1996 more than half of the

employees involved in water and sanitation left their

jobs.

The United States anticipated the collapse of the Iraqi

water system early on. In January 1991, shortly before

the Persian Gulf War began and six months into the

sanctions, the Pentagon's Defense Intelligence Agency

projected that, under the embargo, Iraq's ability to

provide clean drinking water would collapse within six

months. Chemicals for water treatment, the agency noted,

"are depleted or nearing depletion," chlorine

supplies were "critically low," the main

chlorine-production plants had been shut down, and

industries such as pharmaceuticals and food processing

were already becoming incapacitated. "Unless the

water is purified with chlorine," the agency

concluded, "epidemics of such diseases as cholera,

hepatitis, and typhoid could occur." All of

this indeed came to pass.

MEDICAL EQUIPMENT

As of last March, there were $25 million worth of holds

on contracts for hospital essentials sterilizers, oxygen

plants, spare parts for basic utilities that,

despite release by UNMOVIC, were still blocked by the

United States on the claim of "dual use."

As of September 2001, nearly a billion dollars'

worth of medical-equipment contracts for which all

the information sought had been provided was still

on hold.

In the late 1980s the mortality rate for Iraqi

children under five years old was about fifty per

thousand. By 1994 it had nearly doubled, to just under

ninety. By 1999 it had increased again, this time to

nearly 130; that is, 13 percent of all Iraqi children

were dead before their fifth birthday. For the most part,

they die as a direct or indirect result of contaminated

water.

It is no accident that the operation of the 661

Committee is so obscured. Behind closed doors, ensconced

in a U.N. bureaucracy few citizens could bypass.

American policymakers are in a good position to avoid

criticism of their practices; but they are also, rightly,

fearful of public scrutiny, as a fracas over a block on

medical supplies last year illustrates.

In early 2001, the United States had placed holds

on $280 million in medical supplies, including vaccines

to treat infant hepatitis, tetanus, and diphtheria, as

well as incubators and cardiac equipment. The rationale

was that the vaccines contained live cultures, albeit

highly weakened ones. The Iraqi government, it was

argued, could conceivably extract these, and eventually

grow a virulent fatal strain, then develop a missile or

other delivery system that could effectively disseminate

it. UNICEF and U.N. health agencies, along with other

Security Council members, objected

strenuously. Despite pressure behind the scenes from the

U.N. and from members of the Security Council, the United

States refused to budge. But in March 2001, when the

Washington Post and Reuters reported on the holds

and their impact the United States abruptly

announced it was lifting them.

"smart

sanctions,"

The idea behind smart sanctions is to "contour"

sanctions so that they affect the military and the

political leadership instead of the citizenry. Subsequently

basic civilian necessities, the State Department claimed,

would be handled by the U.N. Secretariat, bypassing the

Security Council. Critics pointed out that in fact

the proposal would change very little since everything

related to infrastructure was routinely classified as

dual use, and so would be subject again to the same kinds

of interference. What the "smart sanctions"

would accomplish was to mask the U.S. role. After the

embarrassing media coverage of the child-vaccine debacle,

the State Department was eager to see the new system in

place, and to see that none of the other permanent

members of the Security Council Russia, Britain,

China, and France vetoed the proposal.

In the end, China and France agreed to support the

U.S. proposal. But Russia did not, and immediately after

Russia vetoed it, the United States placed holds on

nearly every contract that Iraq had with Russian

companies.

GOODS REVIEW LIST

Then last November, the United States began lobbying

again for a smart-sanctions proposal, now called the

Goods Review List (GRL). The proposal passed the Security

Council in May 2002, this time with Russia's support.

In what one diplomat, anonymously quoted in the Financial

Times of April 3, 2002, called "the boldest move yet

by the U.S. to use the holds to buy political

agreement," the Goods Review List had the effect of

lifting $740 million of U.S. holds on Russian contracts

with Iraq, even though the State Department had earlier

insisted that those same holds were necessary to prevent

any military imports. Under the new system, UNMOVIC

and the

International Atomic Energy Agency make the initial

determination about whether an item appears on the GRL,

which includes only those materials questionable enough

to be passed on to the Security Council. The list is

precise and public, but huge. Cobbled together from

existing U.N. and other international lists and

precedents, the GRL has been virtually customized to

accommodate the imaginative breadth of U.S. policymakers'

security concerns.

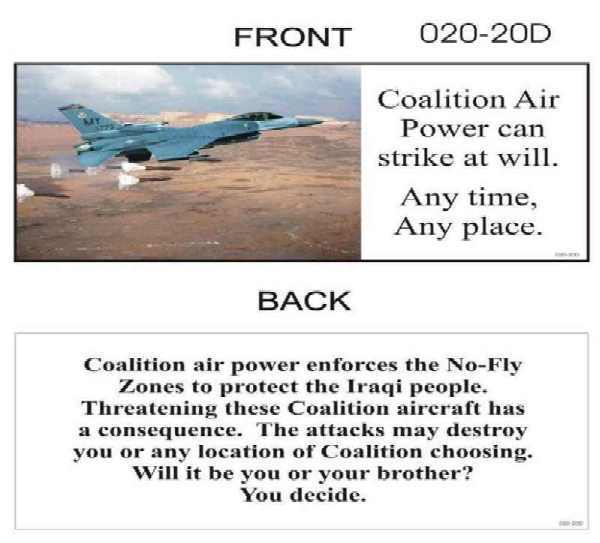

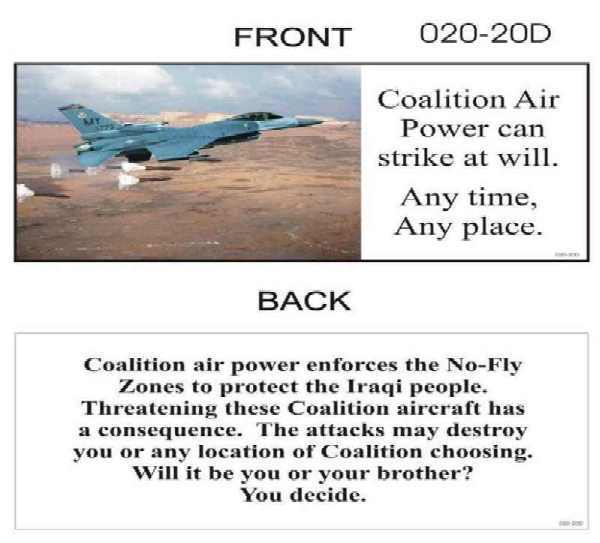

Propaganda ?

When U.N. weapons experts began reviewing the $5 billion

worth of existing holds last July, they found that very

few of them were for goods that ended up on the GRL or

warranted the security concern that the United States had

originally claimed. As a result, hundreds of holds have

been lifted in the last few months.

In December 2000, the Security Council passed a

resolution allowing Iraq to spend 600 million

euros (about $600 million) from its oil sales on

maintenance of its oil-production capabilities. The

United States and Britain devised a system that had the

effect of undermining Iraq's basic capacity to sell oil:

"retroactive pricing." Taking advantage of the

fact that the 661 Committee sets the price Iraq receives

from each oil buyer, the United States and Britain began

to systematically withhold their votes on each price

until the relevant buying period had passed. The idea

was that then the alleged surcharge could be subtracted

from the price after the sale had occurred, and that

price would then be imposed on the buyer. The effect of

this practice has been to torpedo the entire Oil for Food

Programme. Obviously, few buyers would want to commit

themselves to a purchase whose price they do not know

until after they agree to it. As a result of this system,

Iraq's oil income has dropped 40 percent since last year,

and more than $2 billion in humanitarian contracts

all of them fully approved are now stalled.

*********************************************************************

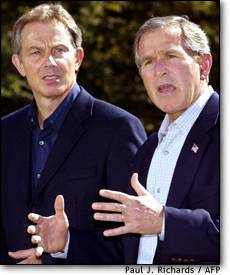

Can we now depend on

the  united nations to come to an equable

and just decision about the usa's desired war on iraq

when they have allowed the usa and britain, by a

technical rule, incapacitate and destroy that nation ?? united nations to come to an equable

and just decision about the usa's desired war on iraq

when they have allowed the usa and britain, by a

technical rule, incapacitate and destroy that nation ??

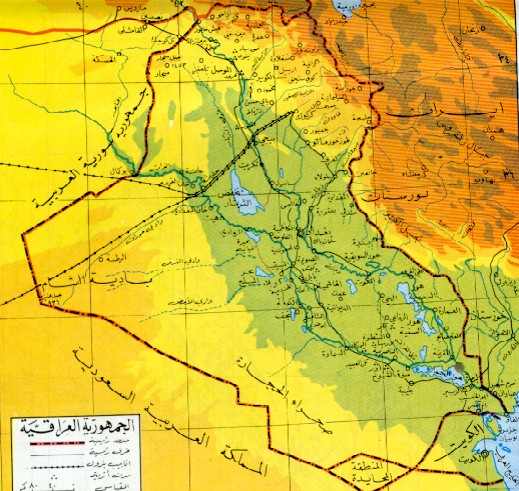

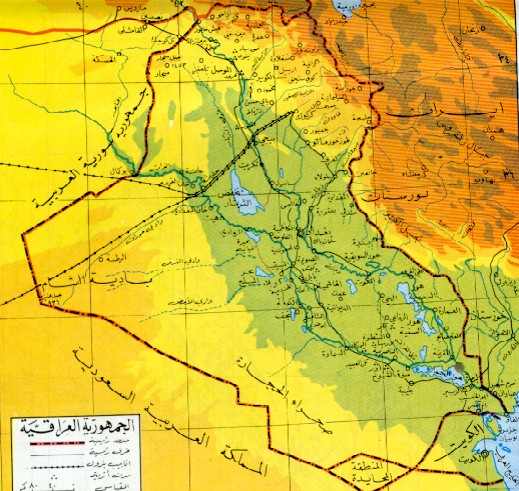

Iraq

Population:

21,422,292 Density:128 per Sq.

Mi Area: 167,975 Sq. Mi (438,317 sq.

km)

Ethnic Groups:

Arab 80% and Kurds 15%, Others 5%

Languages:

Arabic (official), Kurdish, Assyrian, Chaldian, Armenian

Religions:

Muslims 97% (Shi'a 60%, Sunni 37%), Christians 3%

Government

Type: Republic.

Head

of State: President Saddam Hussein

Local

Divisions: 18 Provinces

|

Weapon of Mass Destruction

Weapon of Mass Destruction

Many members

of the Security Council have been sharply critical of

these practices. In an April 20, 2000, meeting of the

661 Committee, one member after another challenged the

legitimacy of the U.S. decisions to impede the

humanitarian contracts. The problem had reached "a

critical point," said the Russian delegate; the

number of holds was "excessive," said the

Canadian representative; the Tunisian delegate expressed

concern over the scale of the holds. The British and

American delegates justified their position on the

grounds that the items on hold were "dual use"

goods that should be monitored, and that they could not

approve them without getting detailed technical

information. The French delegate suggested, that

providing prompt, detailed technical information was not

sufficient to get holds released: a French contract for

the supply of ventilators for intensive care units

had been on hold for more than five months, despite his

government's prompt and detailed response to a request

for additional technical information and the obvious

humanitarian character of the goods.

Many members

of the Security Council have been sharply critical of

these practices. In an April 20, 2000, meeting of the

661 Committee, one member after another challenged the

legitimacy of the U.S. decisions to impede the

humanitarian contracts. The problem had reached "a

critical point," said the Russian delegate; the

number of holds was "excessive," said the

Canadian representative; the Tunisian delegate expressed

concern over the scale of the holds. The British and

American delegates justified their position on the

grounds that the items on hold were "dual use"

goods that should be monitored, and that they could not

approve them without getting detailed technical

information. The French delegate suggested, that

providing prompt, detailed technical information was not

sufficient to get holds released: a French contract for

the supply of ventilators for intensive care units

had been on hold for more than five months, despite his

government's prompt and detailed response to a request

for additional technical information and the obvious

humanitarian character of the goods. Among the many deprivations Iraq

has experienced, none is so closely correlated with

deaths as its damaged water system. Prior to 1990, 95

percent of urban households in Iraq had access to potable

water, as did three quarters of rural households. Soon

after the Persian Gulf War, there were widespread

outbreaks of cholera and typhoid diseases that had

been largely eradicated in Iraq as well as massive

increases in child and infant dysentery, and skyrocketing

child and infant mortality rates. By 1996 all

sewage-treatment plants had broken down. As the state's

economy collapsed, salaries to state employees stopped,

or were paid in Iraqi currency rendered nearly worthless

by inflation. Between 1990 and 1996 more than half of the

employees involved in water and sanitation left their

jobs.

Among the many deprivations Iraq

has experienced, none is so closely correlated with

deaths as its damaged water system. Prior to 1990, 95

percent of urban households in Iraq had access to potable

water, as did three quarters of rural households. Soon

after the Persian Gulf War, there were widespread

outbreaks of cholera and typhoid diseases that had

been largely eradicated in Iraq as well as massive

increases in child and infant dysentery, and skyrocketing

child and infant mortality rates. By 1996 all

sewage-treatment plants had broken down. As the state's

economy collapsed, salaries to state employees stopped,

or were paid in Iraqi currency rendered nearly worthless

by inflation. Between 1990 and 1996 more than half of the

employees involved in water and sanitation left their

jobs.

united nations to come to an equable

and just decision about the usa's desired war on iraq

when they have allowed the usa and britain, by a

technical rule, incapacitate and destroy that nation ??

united nations to come to an equable

and just decision about the usa's desired war on iraq

when they have allowed the usa and britain, by a

technical rule, incapacitate and destroy that nation ??