JULY 2006

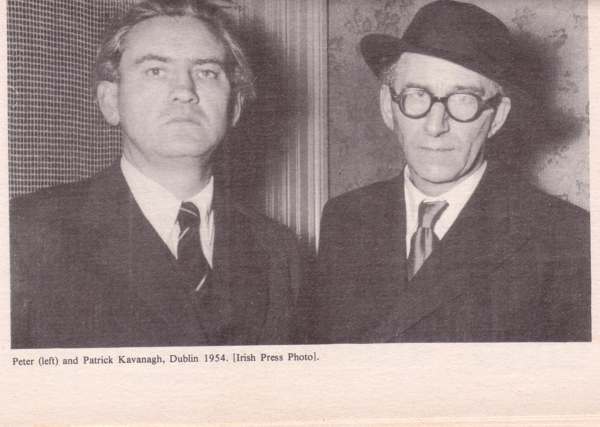

Dr. Peter Kavanagh.

I was acquainted with Dr. Peter Kavanagh only briefly in the last year, 2005, of his life; longer with his writings on the theatre and longer still in curiousity as to who this brother of the poet, Patrick Kavanagh, could be – whom a posse of writers and artists used abuse in conversation.

Peter Kavanagh wrote

extensively on the theatre in Ireland in two volumes, and

he wrote with persuasive authority and lively opinion. As

Patrick, ( whose family always used his name, Patrick,

and never "Paddy" in the hated Dublin

vernacular) wrote to his brother in reference to his

manuscript of The History of The Abbey Theatre

"...the Higgins-O'Connor

time is vivid and alive and shows that it excited you.

Your personality comes through and the author's

personality is an important part of the truth."

In addition in this volume he revealed immense

persistence investigating abstruse or difficult texts of

reference. Singularly, he examined the scarcely

penetrable handwritten diaries of Joseph Holloway and

mined treasures of the past.

Peter and Patrick developed a brotherly unity of purpose

that is quite remarkable. For all the times Peter's

criticism of Patrick's texts written and re-written,

Paddy too gave as good as he got. Regarding the reference

above Paddy gave the ms. strong abuse though alleviating

the blow in a postscript - "When I look through

it again I change my mind." However this led to

a scrutiny of the text by Peter and an editor of

Garrity's which discarded 15,000 words ! This History of

the Abbey Theatre as it reads now is a powerful appraisal

of Yeats dedication to a poetic ideal. The New York Times

Book Review, such an important source for thousands of

American tourist audiences in that theatre,described the

book as an impartial history and the best book written on

the subject.

Peter Kavanagh shared with his brother in his youth a

strong interest in mythology of the area in which they

were born - on the threshold of the history of Cuchulain,

in sight of the Gap of the North through which armies

both from and into Ulster marched, in the vicinity of the

sacred mountain, Slieve Gullion. Peter wrote a small book

at the death of his brother about their townlands. He

also wrote a Dictionary of Irish Mythology and there

Patrick wrote :

"I never felt the same, or anything like it,

about any Christian shrine. The shrines were literal. No

miracles...all the miracles were pagan miracles and

touched with pantheism..........The satisfying quality in

these ideas is the absence of limits. They project beyond

mortality. The soul must expand or die...."

You may be thinking that I touch lightly on the

history of this man whose relationship with his brother

presents us unequivocally with Patrick Kavanagh's poems,

letters and texts. But this is the writing, with much of

his emotion, in both specific texts and the quality of

expression throughout, that Peter Kavanagh was involved

in. He was responsible for urging his brother, crucially,

to work on his two great poems The Great Hunger

and Lough Derg.

In schools here in Ireland of the much loved poems

in the school syllabus, the children perhaps only hear of

Dr. Kavanagh creating with his brother Kavanagh's

Weekly, the thirteen issues of which

invaded the stultifying atmosphere of literary academic

rigor mortis that then pervaded Dublin. Writing completed

under several pseudonyms and covering with outspoken

opinion the events of the time, 1952.

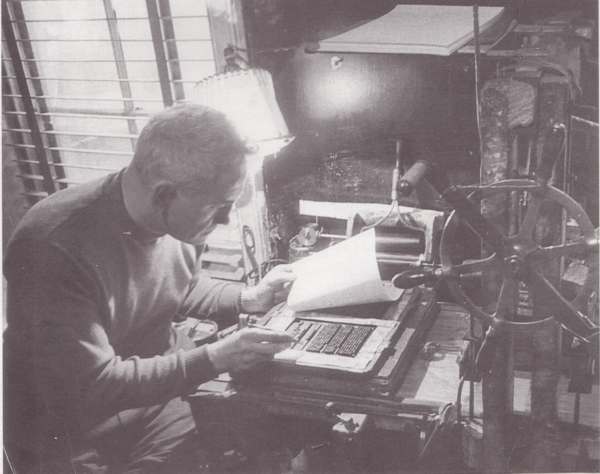

But Peter Kavanagh's own academic career brought him much

satisfaction - he moved to America where he taught in

Universities in Chicago, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin as

Professor of Modern Poetry. In 1958, maintaining a

residence in New York, he built his own Printing Press

with one purpose in mind - to print poems of Patrick's

that were being ignored by commercial publishers, and to

print the first ever volume of Patrick Kavanagh's

Collected Poems. He never let his close association with

Patrick drop as can be confirmed in hundreds of letters

collected in Lapped Furrows, another of his

publications in later years. Building this press he says:

I made it out of wood with two aliminium plates half an

inch thick, attached to an old (1893) Singer sewing

machine which I bought for five

dollars.................it will take a little

experimentation to get the bugs out of my press but I

will eventually manage that...........It will take me

some time to set a book, for I will have type for only

one page at a time." Later that year he wrote

to Patrick: I have now mastered my Press - never have

I tackled a more difficult job ..........I am not

stopping now that I have got started.... though learning

a trade in weeks that normally takes years.

Such was his eagerness to print a volume of his brother's

work. He finally threw this press on to the street in

August 1962 and planned to install a commercial press in

an appartment."Hand setting (of the print)

is beautiful, but the work involved is beyond the beyonds

- I had to stop using my fingers." (However,

his widow, Mrs Anne Keeley Kavanagh, tells me that this

press was never thrown out except for pieces of it that

were discarded for improved replacements; and this Press

can now be seen in the Kavanagh Museum.)

Peter Kavanagh had graduated from the National University

of Ireland in 1941 and obtained a Ph.D from Trinity

College in 1944. He began his teaching career with the

Christian Brothers at Westland Row, Dublin, "a

barbarous environment,"where after a dispute

with a school inspector he was pushed into a dark

discarded classroom with 50 pupils. Of that time George

Coughlan, a pupil, wrote in later years:

"I can still sing those rebel songs you taught

us on your clarinet and you gave me an interest in

Theatre, literature and Music that persisted. It was the

most delightful year - the only time I received any

genuine education."

After his brother's death Peter began publishing a series

of books on his brother's life. He also published his Dictionary

of Irish Mythology and his autobiography Beyond

Affection.

We can say that Peter Kavanagh's life work, devoted

as it seems almost entirely to his brother's life

nevertheless also shows an author of importance and

authority. His volumes on the History of the Irish

Theatre and The History of the Abbey Theatre

are acclaimed texts both academically and of personal

vision. He stressed that Yeats brought about an original

theatre of the highest integrity dedicated to a poetic

ideal.

The Abbey Theatre was a dream in the mind of Yeats.

He made it a reality during his life, but when he died

the reality returned to the dream and passed away with

its creator. And elsewhere:He was guided always

by intuition, rarely by reason or expedience.

In addition he wrote of Sean O'Casey: "He was

Ireland himself - who wrote sincerely only out of his own

life and emotions. He was expressing the inner spirit of

Ireland. Dublin tenement dwellers are the most

essentially Irish group in the nation. He (O'Casey)

does not have to fight off that savage love of the soil

which would engulf the spirit. " and elsewhere:

"Dublin, while it produces writers has no sympathy

for them - and it is difficult to survive there and

produce good work"

In reference to one of Joseph Holloway's Diary entries he

amusingly quotes: "Yeats gave instructions for

the minimum of action - be statuesque - the actors spoke

to the audience instead of each other with their heads on

the side as if they had boils on their necks." Holloway

was surely a man after Peter's heart, he wrote of the

police attendances during performances of The Playboy of

the Western World - "This was freedom of the

theatre, according to Yeats, and his studies in blue

ranged along the walls like Tussaud's Waxworks." Or,

again, Holloway on St.John Ervine - "When a

Northener has talent combined with cheek there is no

holding him..."

Despite the difficulties of working under Edward

Martyn the theatre continued also after Yeats death to

give its best shots and Peter was able to confirm this

from his own experience in 1930 when he attended all its

productions, both new plays and revivals. Peter's high

excitement with theatre informs his exceptional ability

to re-create that excitement, and understand the

importance of theatrical experience for civilisation,

that sends one off to read or re-read Irish authors from

history to the present time. Writing of George Russel he

says : He (AE) realised that the greatest spiritual

evil one nation could inflict on another was to cut off

from it the story of the national soil.

At this point it is worth remembering those great men

George Petrie, John O'Donovan and Eugene O'Curry who

miraculously, perhaps urged by a spiritual apprehension

of the future, rescued so much of that history and myth

as it really existed among the Irish people in years

prior to the Famine. Any later, investigators would have

missed so much, and it entirely beyond recall. Even then

those fine men experienced that evil of national

repression when the British Authorities prevented them

continuing their geographic surveys of Place Names and

their histories. All the work subsequently was done

almost voluntarily and privately, but by those dedicated

men whose energy never seemed to tire.

I understand that Peter Kavanagh wrote regularly all his

life and it will certainly be of great interest to hear

of future posthumous publications by this sincere strong

man. And as to the scabrous abuse he suffered here in

Ireland, as did his brother Patrick in his time - one

wonders how many of the Irish writers and artists of note

wrote to him in his last years to apologise for their

brutal "brotherhood" of arrogance.

Jocelyn Braddell.