|

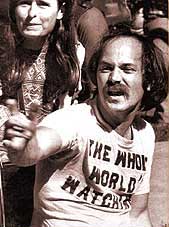

Ron Kovic Reborn

By Tim Gilmer

New Mobility

Monday 23 June 2003

When bad men combine, the good must

associate; else they will fall, one by one." Edmund Burke

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I am the living death

the memorial day on wheels

I am your yankee doodle dandy

your John Wayne come home

your fourth of july firecracker

exploding in the grave

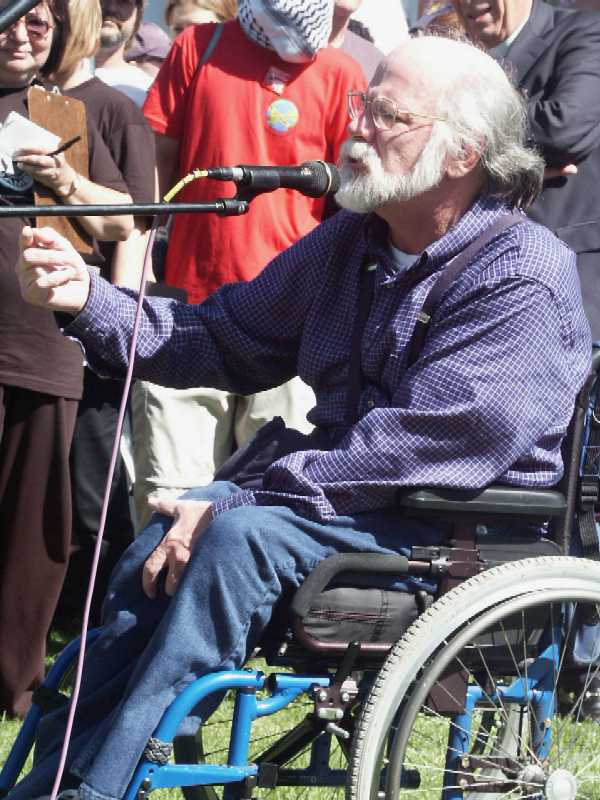

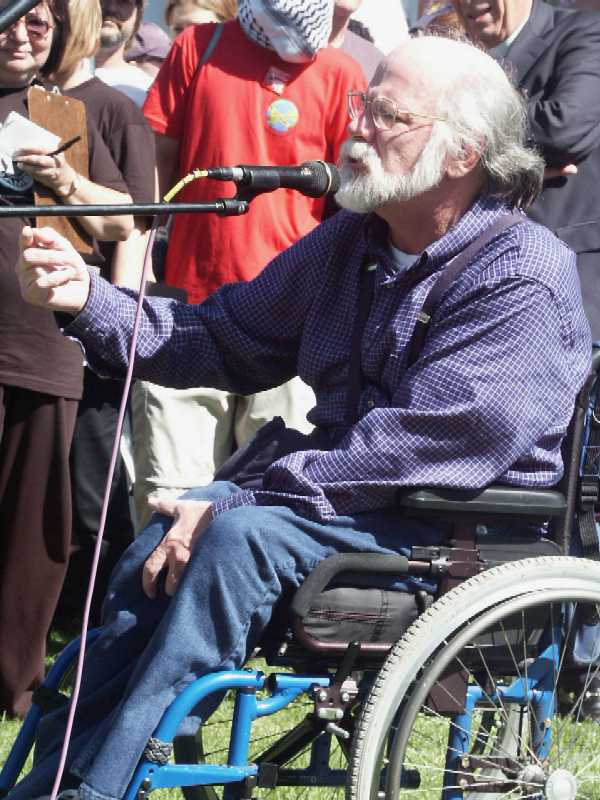

The day Baghdad fell, Ron Kovic was back in the

Veterans Affairs hospital. Not the shameful Bronx VA that

Kovic's 1976 book, "Born on the Fourth of

July," and later, Oliver Stone's academy

award-winning movie of the same name, exposed –

which was subsequently condemned and torn down – but

the Long Beach, Calif., VA hospital. Kovic, 56, had gone

in for a checkup at the spinal cord injury outpatient

clinic, only to find his doctor expressing worry over

potential cutbacks, a situation reminiscent of spending

priorities at the close of the Vietnam War.

"We're putting all of these millions of

dollars into warfare when the disabled of our country,

disabled veterans and disabled citizens, are in need.

Many of them live below the poverty level," says the

man whose life was portrayed onscreen in 1989 by Tom

Cruise. "This policy of aggression, this policy of

arrogance, of blindness, of recklessness, I don't think

this is going to help America. I think that this

behavior, which I abhor, this policy, which I strongly

disagree with, is leading this country in the wrong

direction."

His voice has been shaped by war, its destructive

aftermath and decades of fearless commitment to

protesting governmental policies that support war. To

Kovic, war is not an abstraction, not a neatly packaged

television graphic – The War with Saddam – not

a map bristling with colored pins. It's blood-and-guts

reality, and he owns it. He's a streetwise activist,

"I think this policy is so wrong, and so misguided,

and I may be one of the few Americans saying that right

now, but I believe strongly in what I'm saying, and I'll

say it today, even on this day – [the day Baghdad

fell]. This is a terribly misguided policy that will

backfire, this will not stand, this will not work, this

will work only against us. This will not lead us to peace

and this will not lead us to justice, and this will not

lead us to a safer world but a more dangerous world, a

more dangerous and unstable Middle East. I think this is

going to hurt America."

The Road to Rage

He first spoke out in public against war at

Levittown High School on Long Island, N.Y., in 1969. He

was 23 years old, still adjusting to the T4-6 spinal cord

injury he had sustained in combat in January 1968, still

feeling conspicuous in his wheelchair. It was baptism by

fire. For a Vietnam veteran to speak out against the war

at this time was tantamount to sacrilege, and dangerous:

"All week I had not wanted to go because I had never

spoken in public before, I was very hesitant, and Bob

Muller, who later became the founder of the Vietnam

Veterans of America, had finally convinced me to come

down and join him that day, and I went out on the stage

and there was this bomb threat. We had to evacuate the

auditorium and go out to the grandstands on the football

field. That was quite a beginning for me."

And an even more dramatic turnaround. Kovic had

been a gung-ho Marine who had volunteered to serve a second tour of duty in

Vietnam, a young man whose parents had both served in

World War II, whose uncles had been Marines, who had been

deeply disturbed by growing protests against the war and

who had not hesitated to volunteer for a dangerous

mission the day he was shot. But his experience in the

Bronx VA Hospital opened his eyes. to serve a second tour of duty in

Vietnam, a young man whose parents had both served in

World War II, whose uncles had been Marines, who had been

deeply disturbed by growing protests against the war and

who had not hesitated to volunteer for a dangerous

mission the day he was shot. But his experience in the

Bronx VA Hospital opened his eyes.

"They used to call it the Bronx Zoo. It was

there that I began to wonder why I and the others had

gone to Vietnam in the first place. And whether we had

lost our bodies for nothing. It was in that place going

through the sometimes-abusive conditions that I was

slowly becoming aware and recognizing what had happened.

And I remember seeing all the wounded around me, getting

a full picture, which you never saw, for instance, during

the recent war coverage on CNN or Fox News. You'll never

see what I saw."

What he saw was an understaffed, outdated veterans

hospital teeming with paralyzed bodies, amputees and head

injuries. And why were they being treated like disposable

parts of a machine instead of heroes? The questions

yielded no satisfactory answers, and anger and bitterness

grew in the vacuum. "I'm not ashamed to admit that I

felt enraged," he says.

Not long after leaving the Bronx VA for the second

time, he moved to California, where he was influenced by

author/screenwriter Dalton Trumbo. "I remember

reading his book – 'Johnny Got His Gun' – a

powerful antiwar novel [set in World War I and published

in 1939]. I had just become involved with the vets

against the war, just hesitantly beginning to oppose the

war in 1970-71." Kovic attended the opening of the

movie based on the book, where he met Trumbo and actor

Donald Sutherland. "It was an extraordinary evening,

and I thanked them that night and it was thrilling to

meet Trumbo. He was one of the Hollywood 10, definitely a

man of his conviction, someone I respected." Trumbo,

suspected of having communist ties, was imprisoned for

nearly a year in 1950 for refusing to testify before a

congressional committee, then blacklisted by Hollywood

until the late 1960s. "I really think his book

influenced the very heart and soul of my writing of 'Born

on the Fourth of July.'"

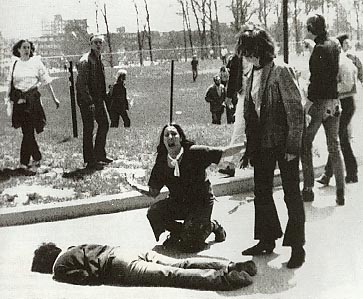

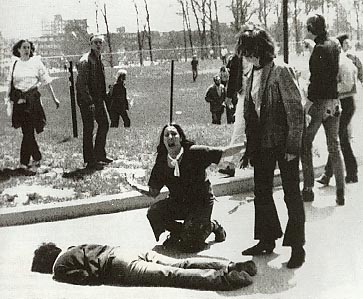

The year prior to the

release of the film version of "Johnny Got His

Gun," National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of

Kent State University students protesting the Vietnam

War, killing four and wounding nine. To this day Kovic

maintains a close connection with Kent State students. In

the late 1970s he was arrested for protesting the

desecration of the site of the massacre and has spoken on

campus a number of times, primarily on the anniversary of

the shootings. "I was deeply affected by what

happened on that date," he says, referring to May 4,

1970 – one of the darkest days of the Vietnam era,

on a par with the infamous My Lai massacre. The year prior to the

release of the film version of "Johnny Got His

Gun," National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of

Kent State University students protesting the Vietnam

War, killing four and wounding nine. To this day Kovic

maintains a close connection with Kent State students. In

the late 1970s he was arrested for protesting the

desecration of the site of the massacre and has spoken on

campus a number of times, primarily on the anniversary of

the shootings. "I was deeply affected by what

happened on that date," he says, referring to May 4,

1970 – one of the darkest days of the Vietnam era,

on a par with the infamous My Lai massacre.

As if witnessing this kind of

government-sanctioned madness weren't enough, Kovic had

to deal with his own personal My Lai – his platoon

had killed innocent villagers. Babies. And then there was

the young corporal from Georgia, who Kovic accidentally

shot and killed in a chaotic firefight.

Add to this the allure of fate: The most important

dates in Kovic's life coincided with two of his country's

most important historic dates. Most people know the

significance of his birthdate from his book or Stone's

movie, but many do not know that he was shot and

paralyzed, in effect reborn as a paralyzed vet, the same

day Martin Luther King Jr. celebrated his last birthday.

He would later choose King as his model for nonviolent

protest in the streets.

That Kovic's birthday falls on the same day his

country celebrates the birth of democracy. As a  child, year after year he

celebrated Independence Day as the high point of his

life: "We'd eat lots of ice cream and watermelon and

I'd open up all the presents and blow out the candles on

the big red, white and blue birthday cake," he

writes in his book, "and then we'd all sing 'Happy

Birthday' and 'I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy.'" The same

kids who attended his birthday party played make-believe

war with him in the woods on the outskirts of Massapequa,

a small town on Long Island. "I grew up with

Sergeant Rock comic books and John Wayne in 'Sands of Iwo

Jima' and Audie Murphy [decorated war hero-turned-actor]

in 'To Hell and Back.' I had grown up with a strong

conditioning concerning the military." child, year after year he

celebrated Independence Day as the high point of his

life: "We'd eat lots of ice cream and watermelon and

I'd open up all the presents and blow out the candles on

the big red, white and blue birthday cake," he

writes in his book, "and then we'd all sing 'Happy

Birthday' and 'I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy.'" The same

kids who attended his birthday party played make-believe

war with him in the woods on the outskirts of Massapequa,

a small town on Long Island. "I grew up with

Sergeant Rock comic books and John Wayne in 'Sands of Iwo

Jima' and Audie Murphy [decorated war hero-turned-actor]

in 'To Hell and Back.' I had grown up with a strong

conditioning concerning the military."

In 1972, protesting with other Vietnam vets at

President Richard M. Nixon's campaign headquarters on

Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, he was thrown from his

chair and kicked, then jailed – by undercover police

pretending to be protesting war veterans. That same year

at the Republican National Convention in Miami, while

attempting to shout down Nixon, he and other veterans

against the war were forcibly removed from the convention

hall. Moments later, a man who would later become the

first president of the United States to resign rather

than be removed from office because of criminal activity

smiled and waved to supporters amid chants of "Four

more years! Four more years!"

Little wonder – when all these influences are

combined – that Kovic's autobiography –

published on the 200th anniversary of the nation –

opens with his darkly ironic poem:

- I am the living death

- the memorial day on wheels

- I am your yankee doodle dandy

- your John Wayne come home

- your fourth of july firecracker

- exploding in the grave

As a political figure, Kovic's star ascended to

the heights of national recognition at the 1976

Democratic National Convention, where he spoke to the

delegates. His journey to the national platform had not

taken him through the usual political pathways. He had

earned his credentials from years of protesting in the

streets and speaking out against the war.

He returned to the Democratic National Convention

as a delegate for Jesse Jackson in 1988. Over the next

three years he co-wrote the film version of "Born on

the Fourth of July," receiving a Golden Globe (on

the anniversary of his having been wounded) for best

screenplay along with Oliver Stone – who also won an

Academy Award for best director – and spoke out

against the Gulf War, giving numerous speeches, press

conferences and interviews, including an appearance on

"The Larry King Show." And of course, he

brought his protest to the streets.

Why did he always return to the path of civil

disobedience? "There was a certain amount of

distrust after I came home from the war, a certain

distrust of the system," he says. "And I think

there was a part of me that would always – as it is

with many combat veterans – have a difficult time

trusting this government. But I had a lot of faith in

people like my mother and father, decent working people,

and I had a lot of faith in grassroots politics, and I

really believed that I could contribute the most by

working outside the system."

There was a moment

when he considered becoming a candidate. "I was

asked to run for office by many people after the movie

came out. I was asked to run against Robert Dornan in

Orange County. I was on his television show twice –

it was quite controversial, it was a shouting match, it

was quite uncomfortable, and that was the closest I came

to ever running. But I made a decision, and I'm glad I

chose not to run. I've always wanted to work outside of

the political process. I've had a very political life,

I've met people across the political spectrum and I've

tried to speak from my heart – and speak as freely

as possible." There was a moment

when he considered becoming a candidate. "I was

asked to run for office by many people after the movie

came out. I was asked to run against Robert Dornan in

Orange County. I was on his television show twice –

it was quite controversial, it was a shouting match, it

was quite uncomfortable, and that was the closest I came

to ever running. But I made a decision, and I'm glad I

chose not to run. I've always wanted to work outside of

the political process. I've had a very political life,

I've met people across the political spectrum and I've

tried to speak from my heart – and speak as freely

as possible."

In the fall of 2002, when talk of war with Iraq

took a serious turn, Kovic again found his voice. "The

true purveyor of terror [is] the government in

Washington, D.C.," he told a crowd of

antiwar marchers he had led to the Army Reserve Center in

Santa Monica, Calif., on Oct. 6 – the first

anniversary of the beginning of the bombing of

Afghanistan. Armed with a bullhorn, Kovic exhorted

National Guardsmen and trainees to lay down their weapons

and join the new peace movement. Earlier, addressing the

protesters, many of whom were UCLA students, Kovic called

the rally "the greatest class in democracy you

can take."

On Oct. 26, elaborating on his vision of a

populist antiwar uprising, Kovic flirted with hyperbole

in addressing a huge crowd of protesters in San

Francisco: "This is the most important moment

in American history. You are a part of an extraordinary

moment in the turning of the history of this country. You

will take this government back on behalf of the people of

the United States." Invoking his idol, King,

he went on to advocate nonviolent protest, placing blame

for the terrorist threat squarely at the feet of the Bush

administration. "The leaders, the president

... they are the ones who have brought on Sept. 11. It is

their violence that brought the violence to our nation,

and it's their violence that we must stop and stop

forever."

With the protest movement growing and

hundreds of thousands expected to march Jan. 18 in

Washington, D.C., Kovic spoke with CNN's Wolf Blitzer.

The interview was posted on cnn.com: "I very much

care about this country. ... This is a weekend that has a

lot of significance to me personally. In the spirit of

Dr. Martin Luther King, in the spirit of nonviolence, not

violence, not war, but in the spirit of nonviolence,

we'll be marching with dignity in great numbers all over

this country. This is a movement, a peace movement that

is going to become a citizens' protest movement unlike

... any movement or protest movement ever seen before in

this country."

The next day Kovic was quoted on the "BBC

News Online" as saying the new peace movement

represented a "revolutionary transformation" in

this country that was as important as the Revolutionary

War of 1776, once again linking his political life to the

nation's birth. However, the demonstrations of Jan. 18

may have been the high point of the movement. Hundreds of

thousands marched in Washington, D.C., San Francisco, Los

Angeles, London, Paris and around the world, but from

this day forward, the number of protesters in the United

States began to diminish.

Still, demonstrations continued right up to the

day U.S. forces invaded Iraq, and Kovic remained in the

thick of it. "We will do everything we can in the

streets of this country to bring the troops back

immediately," he told a rain-drenched crowd in Los

Angeles on March 15, just days before the war began.

"We have much respect for them, and we don't want

them to be used the way my  generation

was." generation

was."

Once U.S. troops drove into Iraqi territory, the

mood of the country changed, but Kovic's resolve remained

constant. "When the war began there was this whole

mentality, this whole conformist mentality to get with it

now, no reason to protest, and I absolutely dismissed

that. We would not have stopped the Vietnam War if we had

not been protesting for many years after the war had

already begun." On March 30, with the war in full

swing, Kovic told another Los Angeles crowd of

protesters: "Many of the people who are architects

of the war haven't experienced war as I did. They're ...

risking the lives of the beautiful men and women that are

our troops. It's shameful."

The day Baghdad fell, April 9, just three weeks

into the war, it seemed to outsiders that the new peace

movement had barely lifted off the ground. Looking back,

did Kovic see what others saw, that no one seemed to be

listening? Was the outcome disappointing? "I've

never been more optimistic," he says . "I think

this is the beginning. I firmly believe this is going to

be the beginning of the changing of this country."

What changes does he foresee? "The awakening of a

new democracy, a participatory democracy like none we've

seen before. I want this to be a country that understands

that its citizenship has not only to do with loving this

country, but also building bridges of friendship and

respect to other cultures and people throughout the

world."

Victim or Victorious?

Kovic's priorities, drawn from his war experience,

are clear. He has produced nearly 1,000 paintings over

the years, donating the proceeds mostly to homeless

veterans. "Yes," he says, "to benefit the

homeless – almost on all occasions – homeless

veterans. I've never sold the art for my own personal

gain. If I've auctioned it, I've auctioned it in Chicago,

San Francisco and here in L.A., for the homeless."

He may not be in the forefront of the fight for

disability rights, but the beginning of his life as a

wheelchair user coincides with the birth of seminal

disability legislation – 1968, the year the

Architectural Barriers Act was passed – and he knows

where the movement is headed. In July 2000, on the 10th

anniversary of the passage of the ADA, Kovic spoke at a

celebration sponsored by the Coalition for a Santa Monica

Disabilities Commission. Reporting on the event for the

Santa Monica Mirror, Hannah Heineman writes, quoting

Kovic: "'There's been talk throughout the country

[of] watering down' the ADA because it gives the [more

than] 43 million Americans with physical and emotional

disabilities 'too much.' He urged the crowd at the

celebration to oppose modifications in the act because

'we [the disabled] have been allowed to sit at the table

of equality in America and we like it.'"

A Man of Ideals

At heart, Kovic remains idealistic, a remarkable

state of mind for a man who was paralyzed in a war he

later came to abhor, a man who has been beaten, spat

upon, and jailed several times while invoking his right

– as an American citizen – to demonstrate in

protest. Ironically, at times he sounds like a

wet-behind-the-ears candidate, someone who has yet to

experience the hard realities of politics, or life:

"I believe in democracy – an authentic

democracy where all the people are represented – and

I want to be a part of that, I want to be a part of the

continuation of that great democratic experiment. I want

to expand our democracy, I want to make it more and more

authentic, I want people to be encouraged to speak their

minds and not to be afraid or be intimidated."

Why, then, didn't he support the military's

mission to free Iraq from decades of fear and oppression

by Saddam Hussein and the Baath Party? Doesn't he see the

inconsistency in opposing a war to "free the Iraqi

people" while campaigning for a "true"

democracy here in America? "No, I don't at all. I

think what the military has done is sow the seeds of

discontent all throughout the Middle East. I think that

we really were denied a lot of what was happening during

that war by our media. We weren't able to see all of the

civilian wounded, the many casualties that occurred, and

most of the Arab world was seeing that. This war has

caused a tremendous amount of anger, a tremendous amount

of rage against this country. And I'm offended by that.

I'm offended by what this administration and this

president have done to our name. Now they may be telling

us that we're freeing the Iraqis, but I truly believe in

my heart that President Bush has established – with

the use of brutality and force and violence – a

colony, an American colony in the Middle East. I think

it's shameful."

Kovic's assessment of the Bush administration's

motives does not stop with allegations of colonialism.

The real prize, he says, lies beneath the desert sands.

"I don't think that they will ever allow a

democratic government, because a democratic government

would be a direct threat to the very reason they went

over there to begin with, and that is to dominate the

oil, to control that region, and to literally steal the

resources of that region for this administration, for the

corporations and the businesses of our country. That is a

crime."

Working outside the system while seeking to

influence public opinion and governmental policy has

never been easy, but this latest campaign for peace has

been particularly draining on Kovic. If his life were to

be made into a movie today, Tom Cruise could no longer

play the part. It would take an older actor, someone

whose make-up would neatly transform him into Kovic's

image – bald, with a fringe of white hair and a

beard to match. "This is hard what I do, this is

tiring, it's exhausting," he says. "I've been

right in front and I've been speaking in many places, and

I've been speaking with a tremendous amount of passion.

It can make a person weary. I've given everything I

have."

When civil order has returned to Iraq and a new

government is in place, will he continue to speak out in

protest? More than likely. But his chosen form of

expression may change. He has plans to return to what

launched his career as a public figure: "I have to

remind you and others that I'm also an author and a

writer and I have a love of the language. There are many

ways to communicate my politics, whether it's a motion

picture or the writing of a book or speaking behind a

microphone in a rally. I want to move into writing

another book, a book that I actually was beginning just

before Sept. 11 happened."

Kovic's lifestyle will most likely not stand in

the way of his plans. He lives alone in a Redondo Beach,

Calif., apartment and has never married. "Would I

like to get married someday?" he asks, anticipating

the question. "Yes I would, still. But that's been a

struggle, it's been a challenge."

On July 4, 2003, when America marks its 227th

birthday, Ron Kovic – whether he celebrates his own

birthday in the company of friends or alone with his

thoughts – will once again ponder the meaning of his

personal journey. He will take stock of the man he once

was and the man he has become. And he will consider the

legacy he leaves, personal as well as political. "I

want to be a  voice, I want to be

able to say I did something with my life, in all aspects:

I learned to make love, I learned to accept my body and

feel comfortable with myself, I learned to move about in

this society and feel a part of it. I did something with

my life, and I was able to help others along the

way." voice, I want to be

able to say I did something with my life, in all aspects:

I learned to make love, I learned to accept my body and

feel comfortable with myself, I learned to move about in

this society and feel a part of it. I did something with

my life, and I was able to help others along the

way."

Mr. Kovic contributed this letter for the American

people to the MY HERO web site on Sept. 14, 2001.

Dear Friends,

My heart and soul weeps with everyone in America right

now. I was deeply saddened by the terrible tragedy that

occurred on Sept. 11, 2001. I didn't sleep much

again last night, as it's been for me, and I'm sure so

many others since Tuesday. I wonder if we will ever sleep

"normally" again? I have thought about it a lot

and I am deeply disheartened by the blind patriotism,

hatred and desire for revenge that I see growing more and

more in this country each day. Resorting to violence and

warfare is a great mistake. The painful anguish resulting

from this senseless act of violence stirs in all of us a

desire for swift retribution. I strongly believe that to

move in this direction will lead us into a terrible and

disastrous war which we, as a people and a nation, may

never recover from. It is a dark and dangerous time in

America, and I, in good conscience, will never support

such an act of madness! We seem to have learned nothing

from Vietnam, and those of us who have come to understand

through great suffering the awful waste and deep

immorality of war, are not being listened to. Those of us

who have found that love and forgiveness are more

powerful than hatred are not being heard. We remain

invisible, isolated and alone, voices in the wilderness

in a country that has truly gone mad. I encourage all of

you to raise your voices on behalf of peace and

non-violence everywhere. I love this country so much that

I don't want to see it go through the senselessness and

agony of war ever again.

With love and a sincere hope for peace!

Ron Kovic

"Peace

cannot be achieved through violence, it can only be

attained through understanding."

Albert Einstein

|

to serve a second tour of duty in

Vietnam, a young man whose parents had both served in

World War II, whose uncles had been Marines, who had been

deeply disturbed by growing protests against the war and

who had not hesitated to volunteer for a dangerous

mission the day he was shot. But his experience in the

Bronx VA Hospital opened his eyes.

to serve a second tour of duty in

Vietnam, a young man whose parents had both served in

World War II, whose uncles had been Marines, who had been

deeply disturbed by growing protests against the war and

who had not hesitated to volunteer for a dangerous

mission the day he was shot. But his experience in the

Bronx VA Hospital opened his eyes.  The year prior to the

release of the film version of "Johnny Got His

Gun," National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of

Kent State University students protesting the Vietnam

War, killing four and wounding nine. To this day Kovic

maintains a close connection with Kent State students. In

the late 1970s he was arrested for protesting the

desecration of the site of the massacre and has spoken on

campus a number of times, primarily on the anniversary of

the shootings. "I was deeply affected by what

happened on that date," he says, referring to May 4,

1970 – one of the darkest days of the Vietnam era,

on a par with the infamous My Lai massacre.

The year prior to the

release of the film version of "Johnny Got His

Gun," National Guardsmen opened fire on a crowd of

Kent State University students protesting the Vietnam

War, killing four and wounding nine. To this day Kovic

maintains a close connection with Kent State students. In

the late 1970s he was arrested for protesting the

desecration of the site of the massacre and has spoken on

campus a number of times, primarily on the anniversary of

the shootings. "I was deeply affected by what

happened on that date," he says, referring to May 4,

1970 – one of the darkest days of the Vietnam era,

on a par with the infamous My Lai massacre.  child, year after year he

celebrated Independence Day as the high point of his

life: "We'd eat lots of ice cream and watermelon and

I'd open up all the presents and blow out the candles on

the big red, white and blue birthday cake," he

writes in his book, "and then we'd all sing 'Happy

Birthday' and 'I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy.'" The same

kids who attended his birthday party played make-believe

war with him in the woods on the outskirts of Massapequa,

a small town on Long Island. "I grew up with

Sergeant Rock comic books and John Wayne in 'Sands of Iwo

Jima' and Audie Murphy [decorated war hero-turned-actor]

in 'To Hell and Back.' I had grown up with a strong

conditioning concerning the military."

child, year after year he

celebrated Independence Day as the high point of his

life: "We'd eat lots of ice cream and watermelon and

I'd open up all the presents and blow out the candles on

the big red, white and blue birthday cake," he

writes in his book, "and then we'd all sing 'Happy

Birthday' and 'I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy.'" The same

kids who attended his birthday party played make-believe

war with him in the woods on the outskirts of Massapequa,

a small town on Long Island. "I grew up with

Sergeant Rock comic books and John Wayne in 'Sands of Iwo

Jima' and Audie Murphy [decorated war hero-turned-actor]

in 'To Hell and Back.' I had grown up with a strong

conditioning concerning the military."

There was a moment

when he considered becoming a candidate. "I was

asked to run for office by many people after the movie

came out. I was asked to run against Robert Dornan in

Orange County. I was on his television show twice –

it was quite controversial, it was a shouting match, it

was quite uncomfortable, and that was the closest I came

to ever running. But I made a decision, and I'm glad I

chose not to run. I've always wanted to work outside of

the political process. I've had a very political life,

I've met people across the political spectrum and I've

tried to speak from my heart – and speak as freely

as possible."

There was a moment

when he considered becoming a candidate. "I was

asked to run for office by many people after the movie

came out. I was asked to run against Robert Dornan in

Orange County. I was on his television show twice –

it was quite controversial, it was a shouting match, it

was quite uncomfortable, and that was the closest I came

to ever running. But I made a decision, and I'm glad I

chose not to run. I've always wanted to work outside of

the political process. I've had a very political life,

I've met people across the political spectrum and I've

tried to speak from my heart – and speak as freely

as possible."  generation

was."

generation

was."  voice, I want to be

able to say I did something with my life, in all aspects:

I learned to make love, I learned to accept my body and

feel comfortable with myself, I learned to move about in

this society and feel a part of it. I did something with

my life, and I was able to help others along the

way."

voice, I want to be

able to say I did something with my life, in all aspects:

I learned to make love, I learned to accept my body and

feel comfortable with myself, I learned to move about in

this society and feel a part of it. I did something with

my life, and I was able to help others along the

way."