FEBRUARY/MARCH 2006

"Their deaths rise far above the

clamour - their voices insistent still"

President Mary McAleese's speech at UCC yesterday

where she was addressing a conference titled: The long

revolution: the 1916 Rising in context.

HOW GLAD I AM that I was not the mother of adult children

in January 1916. Would my 20-year-old son and his friends

be among the tens of thousands in British uniform heading

for the Somme, or would they be among the few, training

in secret with the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or with

the Irish Volunteers?

Would I, like so many mothers, bury my son this fateful

year in some army's uniform, in a formidably unequal

country where I have no vote or voice, where many young

men are destined to be cannon fodder, and women widows?

How many times did those men and women wonder what the

world would be like in the longer run as a result of the

outworking of the chaos around them, this

context we struggle to comprehend these years later?

I am grateful that I and my children live in the longer

run; for while we could speculate endlessly about what

life might be like if the Rising had not happened, or if

the Great War had not been fought, we who live in these

times know and inhabit the world that revealed itself

because they happened.

April 1916, and the world is as big a mess as it is

possible to imagine.

The ancient monarchies, Austria, Russia and Germany,

which plunged Europe into war, are on the brink of

violent destruction. China is slipping into civil war. On

the Western Front, Verdun is taking a dreadful toll and,

in the east, Britain is only weeks away from its worst

defeat in history. It's a fighting world where war is

glorified and death in uniform seen as the ultimate act

of nobility, at least for one's own side.

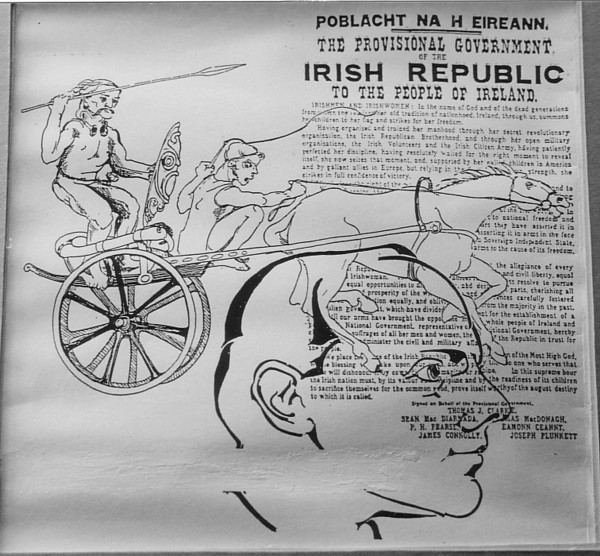

And on the 24th of April, 1916, it was Easter Monday in

Dublin, the second city of the extensive British empire

which long included among its captured dominions the four

provinces of Ireland. At four minutes past noon, from the

steps of Dublin's General Post Office, the president of

the provisional government, Patrick Pearse, read the

Proclamation of Independence.

The bald facts are well known and reasonably

non-contentious. Their analysis and interpretation have

been both continuous and controversial ever since. Even

after 90 years, a discussion such as we are embarked upon

here is likely to provoke someone. But in a free and

peaceful democracy, where complex things get figured out

through public debate, that is as it should be.

With each passing year, post-Rising Ireland reveals

itself, and we who are of this strong independent and

high-achieving Ireland would do well to ponder the extent

to which today's freedoms, values, ambitions and success

rest on that perilous and militarily doomed undertaking

of nine decades ago, and on the words of that

Proclamation.

Clearly its fundamental idea was freedom, or in the words

of the Proclamation, "the right of the Irish people

to the ownership of Ireland". But it was also a very

radical assertion of the kind of republic a liberated

Ireland should become: "The Republic guarantees

religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal

opportunities to all its citizens and declares its

resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the

whole nation and all of its parts cherishing all of the

children of the nation equally. . ."

It spoke of a parliament "representative of the

whole people of Ireland and elected by the suffrages of

all her men and women"- this at a time when

Westminster was still refusing to concede the vote to

women on the basis that to do so would be to give in to

terrorism.

To our 21st-century ears these words seem a good fit for

our modern democracy. Yet 90 years ago, even 40 years

ago, they seemed hopelessly naive, and their long-term

intellectual power was destined to be overlooked, as

interest was focused on the emotionally charged political

power of the Rising and the renewed nationalist fervour

it evoked.

In the longer term the apparent naivety of the words of

the Proclamation has filled out into a widely shared

political philosophy of equality and social inclusion in

tune with the contemporary spirit of democracy, human

rights, equality and anti-

confessionalism. Read now in the light of the liberation

of women, the development of social partnership, the

focus on rights and equality, the ending of the special

position of the Catholic Church, to mention but a few, we

see a much more coherent, and wider-reaching,

intellectual event than may have previously been noted.

The kind of Ireland the heroes of the Rising aspired to

was based on an inclusivity that, famously, would

"cherish all the children of the nation equally -

oblivious of the differences which have divided a

minority from the majority in the past".

That culture of inclusion is manifestly a strong

contemporary impulse working its way today through

relationships with the North, with unionists, with the

newcomers to our shores, with our marginalised, and with

our own increasing diversity.

For many years the social agenda of the Rising

represented an unrealisable aspiration, until now that

is, when our prosperity has created a real opportunity

for ending poverty and promoting true equality of

opportunity for our people and when those idealistic

words have started to become a

lived reality and a determined ambition.

There is a tendency for powerful and pitiless elites to

dismiss with damning labels those who oppose them. That

was probably the source of the accusation that 1916 was

an exclusive and sectarian enterprise. It was never that,

though ironically it was an accurate description of what

the Rising opposed.

In 1916, Ireland was a small nation attempting to gain

its independence from one of Europe's many powerful

empires.

In the 19th century an English radical described the

occupation of India as a system of "outdoor

relief" for the younger sons of the upper classes.

The administration of Ireland was not very different,

being carried on as a process of continuous conversation

around the fire in the Kildare Street Club by past pupils

of public schools. It was no way to run a country, even

without the glass ceiling for Catholics.

Internationally, in 1916, Planet Earth was a world of

violent conflicts and armies. It was a world where

countries operated on the principle that the strong would

do what they wished and the weak would endure what they

must. There were few, if any, sophisticated mechanisms

for resolving territorial conflicts. Diplomacy existed to

regulate conflict, not to resolve it.

It was in that context that the leaders of the Rising saw

their investment in the assertion of Ireland's

nationhood. They were not attempting to establish an

isolated and segregated territory of "ourselves

alone", as the phrase "sinn féin" is so

often mistranslated, but a free country in which we

ourselves could take responsibility for our own destiny,

a country that could stand up for itself, have its own

distinct perspective, pull itself up by its bootstraps,

and be counted with respect among the free nations of

Europe and the world.

A Google search for the phrase "narrow

nationalism" produces about 28,000 results. It is

almost as though some people cannot use the word

"nationalism" without qualifying it by the word

"narrow". But that does not make it correct.

I have a strong impression that to its enemies, both in

Ireland and abroad, Irish nationalism looked like a

version of the imperialism it opposed, a sort of

"imperialism lite" through which Ireland would

attempt to be what the great European powers were - the

domination of one cultural and ethnic tradition over

others.It is easy to see how they might have fallen into

that mistaken view, but mistaken they were.

Irish nationalism, from the start, was a multilateral

enterprise, attempting to escape the dominance of a

single class and, in our case a largely foreign class,

into a wider world.

Those who think of Irish nationalists as narrow miss, for

example, the membership many of them had of a universal

church which brought them into contact with a vastly

wider segment of the world than that open to even the

most travelled imperial English gentleman.

Many of the leaders had experience of the Americas, and

in particular of north America with its vibrant

attachment to liberty and democracy. Others of them were

active participants in the international working-class

movements of their day. Whatever you might think of those

involvements, they were universalist and global rather

than constricted and blinkered.

To the revolutionaries, the Rising looked as if it

represented a commitment to membership of the wider

world. For too long they had chafed at the narrow focus

of a unilateral empire which acted as it saw fit and

resented having to pay any attention to the needs of

others.

In 1973 a free Irish Republic would show by joining the

European Union that membership of a union was never our

problem, but rather involuntary membership of a union in

which we had no say.

Those who are surprised by Ireland's enthusiasm for the

European Union, and think of it as a repudiation of our

struggle for independence, fail to see Ireland's historic

engagement with the European Continent and the Americas.

Arguably Ireland's involvement in the British

Commonwealth up to the Dominion Conference of 1929

represents an attempt to promote Ireland's involvement

with the wider world even as it negotiated further

independence from Britain.

Eamon de Valera's support for the League of Nations, our

later commitment to the United Nations and our long

pursuit of membership of the Common Market are all of a

piece with our earlier engagements with Europe and the

world which were so often frustrated by our proximity to

a strong imperial power - a power which feared our

autonomy, and whose global imperialism ironically was

experienced as narrowing and restrictive to those who

lived under it.

We now can see that promoting the European ideal

dovetails perfectly with the ideals of the men and women

of 1916.

Paradoxically in the longer run, 1916 arguably set in

motion a calming of old conflicts with new concepts and

confidence which, as they mature and take shape, stand us

in good stead today.

Our relationship with Britain, despite the huge toll of

the Troubles, has changed utterly. In this, the year of

the 90th anniversary of the Rising, the Irish and British

governments, co-equal sovereign colleagues in Europe, are

now working side by side as mutually respectful partners,

helping to develop a stable and peaceful future in

Northern Ireland based on the Good Friday agreement.

That agreement asserts equal rights and equal

opportunities for all Northern Ireland's citizens. It

ends for ever one of the Rising's most difficult

legacies, the question of how the people of this island

look at partition.

The constitutional position of Northern Ireland within

the United Kingdom is accepted overwhelmingly by the

electorate North and South. That position can only be

changed by the electorate of Northern Ireland expressing

its view exclusively through the ballot-box.

The future could not be clearer. Both unionists and

nationalists have everything to gain from treating each

other with exemplary courtesy and generosity, for each

has a vision for the future to sell, and a coming

generation, more educated than any before, freer from

conflict than any before, more democratised and

globalised than any before, will have choices to make,

and those choices will be theirs.

This year, the 90th anniversary of the 1916 Rising, and

of the Somme, has the potential to be a pivotal year for

peace and reconciliation, to be a time of shared pride

for the divided grandchildren of those who died, whether

at Messines or in Kilmainham.

The climate has changed dramatically since last

September's historic announcement of IRA decommissioning.

As that new reality sinks in, the people of Northern

Ireland will see the massive potential for their future,

and that of their children, that is theirs for the

taking.

Casting my mind forward to 90 years from now, I have no

way of knowing what the longer term may hold, but I do

know the past we are determined to escape from and I know

the ambitions we have for that longer term.

To paraphrase the Proclamation, we are resolved to

"pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole

island". We want to consign inequality and poverty

to history. We want to live in peace. We want to be

comfortable with, and accommodating of, diversity. We

want to become the best friends, neighbours and partners

we can be to the citizens of Northern Ireland.

In the hearts of those who took part in the Rising, in

what was then an undivided Ireland, was an unshakeable

belief that, whatever our personal political or religious

perspectives, there was huge potential for an Ireland in

which loyalist, republican, unionist, nationalist,

Catholic, Protestant, atheist, agnostic pulled together

to build a shared future, owned by one and all.

That's a longer term to conjure with but, for now,

reflecting back on the sacrifices of the heroes of 1916

and the gallingly unjust world that was their context, I

look at my own context and its threads of connection to

theirs.

I am humbled, excited and grateful to live in one of the

world's most respected, admired and successful

democracies, a country with an identifiably distinctive

voice in Europe and in the world, an Irish republic, a

sovereign independent state, to use the words of the

Proclamation. We are where freedom has brought us.

A tough journey but more than vindicated by our

contemporary context. Like every nation that had to

wrench its freedom from the reluctant grip of empire, we

have our idealistic and heroic founding fathers and

mothers, our Davids to their Goliaths.

That small band who proclaimed the Rising inhabited a sea

of death, an unspeakable time of the most profligate

worldwide waste of human life. Yet their deaths rise far

above the clamour - their voices insistent still.

Enjoy the conference and the rows it will surely rise.

©Irish Times

The Rows that Surely Did Rise !!!

Repackaging and sanitising the

Rising an impossible task

It was essentially nascent fascist sentiments which drove

the leaders of the 1916 Rising, writes Lord Laird.

Exactly 12 months ago in a television interview President

Mary McAleese was comparing the unionist community with

the Nazis. A year on, in a speech delivered at University

College Cork, Mrs McAleese is endeavouring to persuade us

that the 1916 Rising was not sectarian and narrow.

Equally implausibly, she is also claiming that the

content of the Proclamation of 1916 has "evolved

into a widely shared political philosophy of equality and

social inclusion". The principal architect of the

Proclamation, evidenced both by the style and content of

the document, was Patrick Pearse who was also

commander-in-chief of the volunteers and president of the

self-styled provisional government. Far from being a

prophet of "equality and social inclusion",

Pearse - and most of the leaders of the Rising -

subscribed to a dangerous and proto-fascist melange of

messianic Roman Catholicism, mythical Gaelic history and

blood sacrifice.

The head of what purports to be a modern and

progressive European state ought to be extremely wary

of Pearse's almost mystical views on republicanism's

potential as a redeeming force and his contempt for

"the corrupt compromises of constitutional

politics".

In an article entitled The Coming Revolution, published

in December 1913, Patrick Pearse wrote:

"We must accustom ourselves to the thought of arms,

to the sight of arms, to the use of arms. We may make

mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people; but

bloodshed is a cleansing and a sanctifying thing, and the

nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its

manhood. There are many things more horrible than

bloodshed; and slavery is one of them." Are these

really the sort of sentiments - essentially nascent

fascism - which democrats should be celebrating after the

experience of our recent Troubles? In December 1915

Pearse penned the following observation extolling the

bloodshed of the Great War: "It is good for the

world that such things should be done. The old earth

needed to be warmed with the red wine of the

battlefields. Such august homage was never offered to God

as this, the homage of millions of lives given gladly for

love of country."

Are these the values which sensible men and women would

wish to inculcate in the young? It may be a cliche, but

is it not infinitely preferable to teach young people to

live for Ireland rather than die or kill for Ireland? On

Christmas Day, 1915 Pearse wrote: "Here be ghosts

that I have raised this

Christmastide, ghosts of dead men that have bequeathed a

trust to us living men. Ghosts are troublesome things, in

a house or in a family, as we knew even before Ibsen

taught us. There is only one way to appease a ghost. You

must do the thing it asks you. The ghosts of a nation

sometimes ask very big things and they must be appeased,

whatever the cost." Am I alone in finding such views

alarming?

My view is that people who hear such voices should be

dealt with compassionately but be confined in a

high-security mental establishment. Such people should

not be held up to the young as appropriate role models.

In his play, The Singer, Pearse gave expression to his

messianic Roman Catholicism: "One man can free a

people as one Man redeemed the world. I will take no

pike, I will go into the battle with bare hands. I will

stand up before the Gall as Christ hung naked before men

on the tree!" Is this not blasphemy? The 1916

rebellion was profoundly undemocratic. It was essentially

a putsch, not unlike that mounted by Hitler in Munich in

1923. The 1916 rebellion was also unnecessary and a

mistake. What Irish nationalists had sought since the

formation of the Home Rule Party in 1870 was on the brink

of realisation, albeit imperfectly.

Despite the rebellion and the War of Independence, in

broad outline, murder and the mayhem did not improve,

territorially at any rate, the terms which were peaceably

available to John Redmond in 1914. But then, paraphrasing

Pearse's The Coming Revolution, FSL Lyons attributed to

Pearse the view that "nationhood could not be

achieved other than by arms". Fr Francis Shaw went

even further when he observed, almost certainly

correctly: "Pearse, one feels, would not have been

satisfied to attain independence by peaceful means."

An important feature of the rebellion was the rebels'

hostility to all things English and to all things

Protestant, Thomas MacDonagh's enthusiasm

for Jane Austen's novels being a conspicuous, if not

necessarily important, exception. Is this to be cause of

celebration? Mrs McAleese and the Irish Government may be

attempting to challenge the

Provisional Republican movement's claim to be the

undisputed heirs of Easter Week but it may prove to be a

high-risk strategy. How can the 1916 rebellion be

repackaged and sanitised? As Peter Hart in The IRA and

Its Enemies and Richard Abbot in Police Casualties in

Ireland 1919-1922 have amply demonstrated, there is no

valid distinction to be drawn between the murder

and mayhem of the so-called "good old IRA" and

the Provisionals. Murder is murder.

The 50th anniversary of the rebellion in 1966 gave rise

to a lot of irresponsible talk and hot air about

"unfinished business" in the "North".

Such talk coincided with and helped provoke the

re-emergence of political violence in Northern Ireland.

Do Mrs McAleese and Bertie Ahern wish to run the same

risks on the 90th anniversary this year or in 2016? As

realists appreciate, there will not be a united Ireland

in 2016 either.

Lord Laird of Artigarvan is a cross-bench member of

the House of Lords.

...........................................................................

President reinventing our history

David Adams

In her speech at a UCC conference on the 1916

Rising, President Mary McAleese did not so much attempt

to rewrite large chunks of recent Irish history, as try

to reinvent it completely, writes David Adams.

She did not just apply a touch of gloss to some awkward

little pieces of historical furniture, but tried to

deconstruct and refurbish an entire, 90-year, historical

edifice.

According to Mrs McAleese, the Easter Rising was neither

exclusive nor sectarian.

Yet how, other than exclusive, to describe an unelected,

unaccountable, elite embarking on armed insurrection

against the wishes of the vast majority of its fellow

citizens? What appellation, other than sectarian, can be

attached to the subsequent campaign of intimidation,

assault and murder directed against scores of Irish

Protestants on the pretext that, because of their

religion, they must surely be British sympathisers and

collaborators?

To suggest, as the President did, that the 1916 Rising

was inclusive and non-sectarian simply because some women

and a very few highborn Protestants played a part, is

risible.

That is like arguing that the National Party of South

Africa wasn't racist because, as was the case, it had a

tiny sprinkling of ethnic Asians and Africans within its

midst.

Similarly, Mrs McAleese claimed that Irish nationalism

was never narrow. Bizarrely, she based this assertion

largely on the fact that many nationalists "belonged

to a universal church that brought them into contact with

a vastly wider segment of the world than that open to

even the most travelled imperial English gentleman".

There is something deeply ironic in the President taking

a sideswipe at English (notably, not British?)

imperialism while, in the same breath, lauding the

supposed benefits of belonging to a "universal

church" that historically has been more imperial in

outlook and operation than any

nation.

More telling, though, is her failure to recognise that it

was precisely because of its unhealthily close

association with one religious denomination to the

exclusion of all others that Irish nationalism was so

narrow and partial.

President McAleese dismissed those who might have

suspected that post-1916 nationalism would seek "the

domination of one cultural and ethnic tradition over

others", though she did concede that it was easy to

see how people might have "fallen into that mistaken

view".

A "mistaken view"? Did the President not

notice, then, the virtual theocracy that, between them,

the church and a subservient nationalism created and

maintained in Ireland from independence until recent

times?

I agree with President McAleese that today's Republic of

Ireland is a modern, prosperous, democracy with, as she

put it, a widely shared political philosophy of equality,

social inclusion, human rights and anti-confessionalism.

I disagree profoundly, however, with her on how it

arrived at that point. The President would have us

believe that the liberal democracy of today flowed from

the 1916 Proclamation. The truth is that prosperity

flowed directly from Ireland's membership of the European

Union, and liberal democracy from the implosion of an

institution given so much rope in the form of unelected

and unaccountable power and influence, that eventually it

hanged itself.

The 1916 leaders could not possibly have foreseen the

first, or even begun to imagine the second, much less

plan for either.

I have no strong view on whether or not there should be

an official parade to commemorate the 1916 Rising: that

is a matter entirely for the people of the Republic and

their elected representatives. What I do take exception

to, is propaganda posing as historical truth:

irrespective of whether the object is to reclaim a

particular event, elevate a political party or

rehabilitate a religious organisation.

Last Friday, the President did not present a differing

"analysis and interpretation" of recent Irish

history but, rather, a history almost totally divorced

from fact. Far worse, there was nothing in what she had

to say about the "idealistic and heroic founding

fathers and mothers" that could not equally be said

in defence of the Provisional IRA and its actions (or,

for that matter, its would-be successors in the

Continuity and Real IRAs).

After all, they too were a tiny elite of extreme

nationalists who took it upon themselves to drive out the

British at the point of a gun. They too, claimed to be

wedded to the principles of equality and civil and

religious liberty for all, while prosecuting a murderous

campaign against their Protestant neighbours.

If we follow President McAleese's uncritical analysis and

reasoning to its logical conclusion, in intellectual

terms, all that separated the modern IRA from the rebels

of 1916 was the passage of time. To heap retrospective

adulation upon the leaders of the 1916 Rising while

denying it to the Provisionals, is to differentiate only

on the grounds of the relative success of one and

complete failure of the other.

Surely, it is not beyond the President and others to find

a way of celebrating independence without glorifying the

manner in which it was achieved. Until then, nationalism

will continue handing a blank cheque to successive

generations of "freedom fighters".David Adams

..........................................................................

An Irishman's Diary

Underlying the President's dreadful speech at

UCC last weekend was the clear predication that Irish

nationalism was invented with the 1916 insurgency, writes

Kevin Myers.

Thus, wiped from our public history, yet again, were the

achievements of the Irish Parliamentary Party, who two

years before had peacefully secured Home Rule. So Ireland

in 1916 stood on the verge of self-government, once the

Great War was over. Then along came the murderous

lunatics. . .

We cannot remotely guess what path Home Rule Ireland

might have followed without the Rising. But we can

certainly deny that the Irish nationalism resulting from

Easter 1916 was the absurdly benign confection of Mary

McAleese's fantasies: "[not] the domination of one

cultural and ethnic tradition over others", but,

"from the start. . . a multilateral enterprise,

attempting to escape the dominance of a single class, and

in our case a largely foreign class, into a wider

world".

This is utter rubbish. Between 1920 and 1925, some 50,000

Irish Protestants were effectively driven out of the 26

counties. Another 10,000 Protestant artisans left Dublin.

Thousands of (mostly Catholic) RIC men were forced into

exile, and attacks on rural Protestants were widespread

in the new State. When King George VII was crowned in

1938, some of the remaining Protestants in West Cork

gathered in a church to hear the BBC radio report on the

ceremony, with the doors locked, and with sturdy young

men patrolling outside, on the look-out for attack.

That's how confident the Protestant minority felt in the

new "multilateral" Ireland.

Independent Ireland, first under Cumann na nGael, then

Fianna Fáil, became an increasingly intolerant and

confessional State. The sale of condoms, hitherto legal,

was outlawed in 1926, and remained so for nearly 70

years, into the 1990s. The abolition of divorce laws

inherited from the British followed. The official censor,

James Montgomery, deliberately imposed Catholic teaching

on all films. So he cut all mention of divorce from

fictive films, as he frankly confessed, "even if it

spoils the story." The same for "birth

control", or abortion. All references deemed

critical or offensive to the Catholic Church were

similarly cut. And finally, under de Valera, the film

censor's unofficial remit became official government

policy, and the Catholic Church achieved special legal

status not just over cinema, but over the entire State.

The full Monty.

The Celtic Tiger

Thus Ireland retreated from the world, plummeting into

poverty and cultural isolation. As I said recently:

"In 1910, emigration notwithstanding, Ireland was

one of the richest countries in a desperately poor world,

and was more prosperous than, for example, Norway,

Sweden, Italy and Finland. By 1970, self-governing

Ireland, though untouched by the second World War, had

become just about the poorest country in Europe."

For over 50 years, emigration was the destiny for the

majority of Irish-born people.

Moreover, as dismaying as the factual inaccuracy of the

President's address was its smugly sectarianly tribal

silliness. Thus: "Those who think of Irish

nationalism as narrow miss for example, the membership

many of them had of a niversal church which brought them

into contact with a vastly wider segment of the world

than that open to even the most travelled imperial

English gentleman." Now this, surely, is one of the

most fatuous observations in the entire history of the

presidency (Come in, Catholic Paraguay: this is Catholic

Ireland calling). A British imperialist at UCC comparably

alleging that the empire provided a powerful cultural

link between a crofter with his donkey in the Hebrides

and a Mahratta lancer in Poona would have been hooted off

the stage.

The truth is that the post-1916 convergence of both

religion and nationality - the two becoming virtually

indistinguishable by the 1950s - produced a cultural and

economic disaster. Ireland was a bleak and impoverished

madhouse, effectively run by a savage and parasitic caste

of crozier-wielding bishops.

Yet this was an utter contradiction of what pre-1916

Irish nationalism had been or sought: then it had been

neither isolationist nor narrow, and had attracted

widespread Protestant support. (The 1914 Howth and

Kilcoole gun-running operations to the Irish Volunteers,

and the Gaelic revival, were largely Protestant affairs.)

Tom Kettle, Stephen Gwynne, Willie Redmond, John Esmonde

- Irish Parliamentary Party MPs - all enlisted in the

British army in 1914 because they saw it as their duty to

protect a fellow European country against the rapine and

murder inflicted by the Germans in 1914 (who of course by

1916 were the insurgents' "gallant allies").

But the most depressing aspect of the President's direly

chauvinist and reactionary address was that, contemporary

references aside, it could have been made in 1966, as if

all the scholarship and bloodshed of the past decades had

never occurred. Certainly, her allusions to the public

school administrators of Ireland gathering round the fire

at the Kildare Street Club, to the "heroes" in

the GPO, and to the largely (but not quite entirely)

mythical "glass ceiling" for Catholics belong

to the wretchedly simplistic and nationalist caricatures

of 40 years ago.

As insightful as her wretched speech was the balance of

the UCC conference itself, and its complete exclusion of

some serious critics of the Rising - most notably Ruth

Dudley Edwards, The Sunday Independent's superb

columnist, and the author of easily the finest biography

of Pearse. It is absolutely extraordinary, but

dismayingly revealing of the underlying agenda therein,

that she was not even invited. There's another, though

lesser fellow who wasn't asked and who might have made a

minor contribution or two. UCD history graduate. Writes a

fair a bit about 1916: not a fan. But for the life of me,

can't remember his name.

Kevin Myers employed by the

Irish Times to write the columns that were once written

by Miles NaGopaleem author of At Swim Two Birds

...........................................................................

LETTERS TO THE IRISH TIMES:

Madam, - Is it a coincidence that the President chose to

speak on the

subject of the 1916 Rising at a time when the Taoiseach

is planning to

introduce a military commemoration? If Mary Robinson had

ventured into such

terrain during her presidency it would surely have

provoked a constitutional

crisis. Or is it now permissible for the President to

become involved in the

political process? - Yours, etc,

MARGARET LEE,

Ahane,

Newport,

Co Tipperary.

Madam, - President McAleese's speech in Cork has clearly

irked those who

continue to regard her as a Fenian upstart, a tribal

time-bomb or a Croppy

who will not lie down quietly in the former Vice-Regal

Lodge and hold her

whisht, except by royal command. Is the tribute paid to

the 1916

Proclamation of an Irish Republic by the President of

this sovereign

Republic now expected to become some

"post-modern" version of Oscar Wilde's

"love that dare not speak its name"?

People are, of course, entitled to their prejudices. What

is most

extraordinary, however, is Margaret Lee's question

(January 31st) as to

whether it is "now permissible" that the

President "chose to speak on the

subject of the Easter Rising". She completely

ignores the fact that two of

the President's predecessors were themselves Easter

Rising veterans who

annually celebrated that event in full conformity with

the role of President

as envisaged in the Constitution authored by one of them.

Ms Lee fails to appreciate that there has been no

constitutional

counter-revolution in the interim. She proclaims that

"if Mary Robinson had

ventured into such terrain during her presidency it would

surely have

provoked a constitutional crisis". Really? On May

12th, 1996 it was none

other than President Robinson who unveiled the statue of

James Connolly

opposite Liberty Hall, the nerve centre of the 1916

Rising, from which

Pearse and Connolly had led the combined forces of the

Irish Volunteers and

Irish Citizen Army to seize the GPO that Easter Monday.

She declared that

"Connolly was and remains an inspirational figure -

as socialist, as trade

unionist and as Easter Rising leader". She

emphasised how important it was

"to revisit the man and his vision on the 80th

anniversary of his execution,

to reclaim him".

President Robinson went on to speak of "the

relevance of James Connolly to

modern Ireland" and how vital it was to "draw

further inspiration" from "the

emphasis Connolly placed on the values of pluralism and

inclusiveness, until

his death on the 12th of May, 1916".

There was, of course, no "constitutional

crisis". The Rising remains the

common inheritance of the Republic as a whole,

notwithstanding sharp party

divisions, or even the Civil War itself. The Cumann na

nGaedheal president

of the Free State executive, W.T. Cosgrave was no less

proud a 1916 veteran

than the Fianna Fáil leader Eamon de Valera, who would

eventually defeat him

at the ballot box in 1932.

Each had previously been elected to the first Dáil whose

Declaration of

Independence on January 21st, 1919 explicitly stated:

"Whereas the Irish

Republic was proclaimed in Dublin on Easter Monday 1916

by the Irish

Republican Army acting on behalf of the Irish people. . .

and whereas at the

threshold of a new era in history the Irish electorate

has, in the General

Election of December 1918, seized the first occasion to

declare by an

overwhelming majority its firm allegiance to the Irish

Republic; Now,

therefore, we the elected Representatives. . . in

National Parliament

assembled, do, in the name of the Irish nation. . .

ratify the establishment

of the Irish Republic".

In less than three years the 1916 Rising had been

vindicated by the first

ever election held in Ireland based on adult suffrage. It

could have had no

more impressive a democratic validation than that. -

Yours, etc,

MANUS O'RIORDAN,

Head of Research, Siptu,

Liberty Hall,

Dublin 1.

****

Madam, - In an uncharacteristically pacifistic turn,

Kevin Myers pours scorn

on the leaders of the 1916 Rising and accuses those of us

proud to remember

Pearse, Clarke and Connolly as propagating a

"political cult of necrophilia"

(An Irishman's Diary, January 31st).

He asks: "Why had none of the signatories of the

Proclamation, not one of

them, ever stood for parliament?" As a scholar of

the British constitutional

framework, I would have thought Mr Myers capable of

recalling the manner in

which the Act of Union was bought from an utterly

unrepresentative

parliament. The Union was imposed and maintained against

the will of the

Irish people throughout the 19th century, mostly by

legislation that

routinely suspended the rule of law. The privilege of the

minority ruling

class was that it could impose such violent

constitutional change without

bloodshed. So what parliament would Pearse have attended?

Not since the Act of Union had a parliament sat in

Dublin. The best efforts

to establish a parliament based on the principle of Home

Rule were scuppered

by the combined machinations of the British military

officer corps and the

Tories. As early as 1914, it was evident that even if

Home Rule were granted

at the end of the first World War, the country would be

divided.

For whom did the men and women of 1916 speak? The simple

answer is the

people of this country who sought the legitimate goal of

national

self-determination. That the leaders of 1916 were so

removed from a national

mood of independence is not credible when one considers

the results of the

1918 general election. The sweeping victory of Sinn Féin

at the December

polls not alone provides a retrospective legitimacy to

the campaign for

nationhood sparked in Easter Week but proves that the

leaders of 1916 did

not act in a political vacuum.

The murder of combatants on each side was a consequence

of a quest for

national self-determination. Mr Myers refers to the death

of Const James

O'Brien. He fails to mention the murder, in custody, of

the pacifist Francis

Sheehy-Skeffington, on the orders of Colonel

Bowen-Colthurst.

It is only right and fitting that the President of this

country should

declare herself proud of the achievements of the men and

women of 1916.

Unfortunately, the intransigence and fulminations of a

generation of British

politicians, stoked up by a loyalist dimension in the

British high command,

provided little scope for a democratic solution to

Ireland's quest for

independence. Long before Easter 1916, the likelihood of

bloodshed in

Ireland was raised by none other than the combined forces

of the Ulster

Volunteer Force and the staunch unionist ethos of the

British military. -

Yours, etc,

BARRY ANDREWS TD,

Dún Laoghaire,

Co Dublin.

****

Madam, - President McAleese, in her speech on 1916 in

Cork as carried by you

last Saturday, seems to have undone the good work she has

performed over the

past few years on cross-community relations. Or is it a

case of the mask

slipping and the real person coming through, as suggested

by her famous

"Nazi" remarks last year? At least her fellow

Nazi comparisoner, Fr Alec

Reid, has said that he condemns all such uprisings, and

that he wishes 1916

had never taken place.

Mrs McAleese is President for all; and her speech, coming

as it does soon

after the Taoiseach's announcement of a reinstatement of

the military parade

at Easter, leaves me very worried. Now that the Provos

have stopped killing

Protestants, is this a case of it being respectable once

again to

commemorate Pearse and his red blood-sacrifice theories.

For if 1916 is now

justified, why not go the whole hog and celebrate the

murderous campaign

from 1970 onwards which ran out of support and

respectability, to be rescued

perhaps by the peace process? So let's

"celebrate" Enniskillen, Kingsmills,

Le Mon, etc. These too, like 1916, did not have political

justification,

which was sanctified retrospectively.

I well remember the 1916 anniversary in 1966 when we were

treated to an

uncritical treatment of all that went on in 1916 in a

sort of blood and guts

way on RTÉ and elsewhere. Many people believed this

helped to fuel the

Provisionals' campaign a few years later. I had thought

"never again", but

now I am not so sure.

Maybe our President should praise the likes of Parnell,

who, if he had not

been brought down by his own party in collusion with the

Catholic Church,

might have obtained Home Rule for us, and a better

Ireland.

I am so disappointed by Mrs McAleese, and I think she

should consider her

position. - Yours, etc,

BRIAN McCAFFREY,

Clifton Crescent,

Galway.

****

Madam, - In view of the lead given by President

McAleese's commitment to the

ideals of the 1916 Proclamation (guaranteeing "equal

rights and equal

opportunities to all its citizens"), when can we

expect to see lady members

teeing up at Portmarnock? - Yours, etc,

PAT MURPHY,

Greystones,

Co Wicklow.

Madam, - The President's apologia for 1916 (The Irish

Times, January 28th)

cannot gainsay the fact that the men who instigated it

did so without any

mandate from the Irish people to resort to armed force.

Moreover, to

engineer the uprising they deceived their own colleagues,

kidnapped their

friends and resorted to forgery to dupe their commander

in chief, Eoin

MacNeill, into supporting a rising of which they knew he

disapproved. They

had no more mandate to act for the Irish people than John

Redmond had when

he committed some 45,000 young Irishmen to die in the

so-called war for

small nations.

The only person who scrupulously obeyed the basic

democratic republican

imperative - ie, respect for the will of the people,

including,

incidentally, that of his fellow Ulster men and women,

native and planter

stock alike - was Prof Eoin MacNeill, co-founder of the

Gaelic League and

founder and first commander in chief of the Irish

Volunteers, the precursor

of the modern Irish Army.

As CP Curran observed, MacNeill's study window was the

sally port of modern

Irish freedom. Yet this man from the Glens of Antrim

remains forgotten and

ignored by the President and Government of a country

which would have had no

sovereign existence without his decisive intervention at

critical junctures

in its history. It is to be hoped that the Army, at

least, will be spared

the necessity of participating in the commemoration of an

event that

involved the disobeying of the express orders of its

founder and first

commander-in-chief. The Army's celebration should be to

parade each year on

the anniversary of its founding on November 25th, 1913. -

Yours, etc,

MARTIN TIERNEY,

Marlborough Road,

Glenageary,

Co Dublin.

****

Madam, - It would be difficult to overstate the

importance, even profundity,

of the address by President Mary McAleese at UCC last

Friday.

The time had arrived for someone from an elevated

position to bring some

clarity and order to the conflicting and at times

confused thinking on the

validity of the Easter Rising and what followed.

The President is right. The slow confluence of history,

in all its

diversity, has made it possible at last to see some

flowering of many of the

noble political, social and moral precepts set out in the

Proclamation of

1916.

We have now arrived a good deal closer to achieving

"equal rights and

opportunities for all", "religious and civil

liberty", "the happiness and

prosperity of the whole nation", the

"cherishing [of] all the children of

the nation equally" and a parliament

"representative of the whole people of

Ireland and elected by the suffrages of all her men and

women". There is

still much to be done, but the progress is astonishing,

an example of social

and political morality for any other nation that wishes

to attain the

ultimate goal of good governance.

The revisionists also have the right to their views, even

if their vision is

based on what might have been, rather than on what

happened. They also have

the right to express themselves with passion.

Passion can be a dangerous thing. But passion inspired by

insight, reason

and tolerance can be most moving and beautiful. That is

what the President

has achieved.

Unless my head is wrong, her address will receive an

approving response in

the hearts of many people of different political views.

You were so right to

lead your front page with the story and give the full

text of her speech

inside. - Yours, etc,

RORY O'CONNOR,

Rochestown Avenue

Dún Laoghaire

Co Dublin

Illustrations by Jocelyn Braddell