FEBRUARY 2004

Only the Knafeh is still sweet

Sun., January 25, 2004 Shvat 2, 5764 Israel = Time: 02:00 (GMT+2)

By Gideon Levy

NABLUS, West Bank - The knafeh here is still the best in the world, living up to its reputation. In the early evening, Abu Salha's pastry shop, by the side of the road that climbs to the Refidiya neighborhood, is deserted, the shelves almost empty. A salesperson wearing transparent gloves slices the traditional sweet oriental hot cheese delicacy, the taste of which is the only thing that remains unchanged in this beaten and battered city.

From one visit to the next, one sees Nablus declining relentlessly into its death throes. This is not a village that's dying behind the concrete obstacles and earth ramparts that cut it off from the world; this is a city with an ancient history, which until just recently was a vibrant, bustling metropolis that boasted an intense commercial life, a large major university, hospitals, a captivating urban landscape and age-old objects of beauty.

An hour's drive from Tel Aviv, a great Palestinian city is dying, and another of the occupation's goals is being realized. It's not only that the splendid ancient homes have been laid waste, not only that such a large number of the city's residents, many of them innocent, have been killed; the entire society is flickering and will soon be extinguished. A similar fate has visited Jenin, Qalqilyah, Tul Karm and Bethlehem, but in Nablus the impact of the death throes is more powerful because of the city's importance as a district capital and because of its beauty.

A cloud of dust and sand envelops the city, which gives the impression of being a combat zone during a cease-fire; its roads are scarred, its electricity poles and telephone booths are shattered, government buildings have been reduced to heaps of rubble.

But the true wound lies far deeper than the physical destruction: an economic, cultural and social fabric that is disintegrating and a generation that has known only a life of emptiness and despair. More than any other place in the territories, a state of anarchy is palpably close here. There is no city as blocked and sealed as Nablus. For the past three and a half years it has been impossible to maintain even a semblance of ordinary day-to-day life here. It is impossible to leave or enter. Some 200,000 people are prisoners in their city. The checkpoints at Beit Iba, Azmurt and Hawara, which cut off the city from all directions, are the strictest roadblocks in the West Bank. Even women in labor and elderly people have a hard time crossing, and most of the city's residents no longer even try.

Nablus also suffers from a very large number of casualties. In the latest Israel Defense Forces operation in the city, which was given the devilish name of "Still Waters," no fewer than 19 civilians were killed, six of them children, and 200 were wounded, according to a report of the Palestinian Human Rights Monitoring Group. These are the dimensions of a large-scale terrorist attack, only without the public attention, and it's all happening in a period of significant respite in Palestinian terrorism. Who is going to investigate this wholesale killing and the killing of children, including Mohammed Aarj, 6, who was shot while standing in his yard, eating a sandwich? Afterward, the IDF refused to allow an ambulance to evacuate him, according to the Palestinians. Atrocities have been perpetrated here under cover of the total media disregard of the events, residents of Nablus claim.

Neighbors saw Abud Kassim being held by soldiers, and then a gunshot was suddenly heard: he was killed in his yard; Ala Dawiya was found dead with nine bullets in his chest; Fadi Hanani, Jibril Awad and Majdi al-Bash were shot to death at short range, according to the testimonies; the civilian Muain al-Hadi and his cousin Basel were ordered to escort Israeli soldiers as a "human shield," contrary to the explicit ban on the use of this procedure. No one in Israel heard about any of these events and no one will investigate them. Within this reality live tens of thousands of people who have done no wrong. What's being inflicted on them is known as collective punishment and it is considered a war crime. They get up in the morning without knowing what the IDF has wrought in their city during the night and what it will do during the day. Most residents have long since lost their livelihood. Of course, it's possible to argue that they brought it all on themselves because of the terrorist attacks that originated in the city, but that argument cannot justify all the killing and wrongdoing. In the meantime, despite everything, some people are still buying delightful knafeh from Abu Salha.

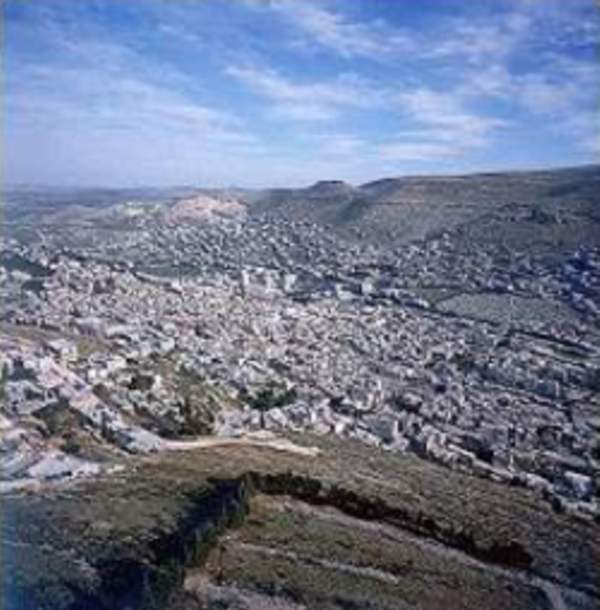

City

of Palestine, located in the

northern part of the West Bank,

with about 240,000 inhabitants (2003 estimate). Nablus is

situated between the mountains of Gerizim amd Ebal.

![]() The economical base for Nablus are industries

producing olive oil, soap, wine and handicrafts. Nablus

is also a trading centre of the produce of its region,

like grapes, olives, wheat and livestock.

The economical base for Nablus are industries

producing olive oil, soap, wine and handicrafts. Nablus

is also a trading centre of the produce of its region,

like grapes, olives, wheat and livestock.

![]() Nablus has biblical

references: In the ancient Canaanite city of Shechem

(with a location close to modern Nablus'), both Abraham

and Jacob are supposed to have lived. The patriarch

Joseph is supposed to have been buried here. Some legends

tell that at the mountain of Gerizim, Moses were given

the 10 commandments, while the mountain of Ebal was used

by him to curse those who defied him and the commandments

of God.

Nablus has biblical

references: In the ancient Canaanite city of Shechem

(with a location close to modern Nablus'), both Abraham

and Jacob are supposed to have lived. The patriarch

Joseph is supposed to have been buried here. Some legends

tell that at the mountain of Gerizim, Moses were given

the 10 commandments, while the mountain of Ebal was used

by him to curse those who defied him and the commandments

of God.

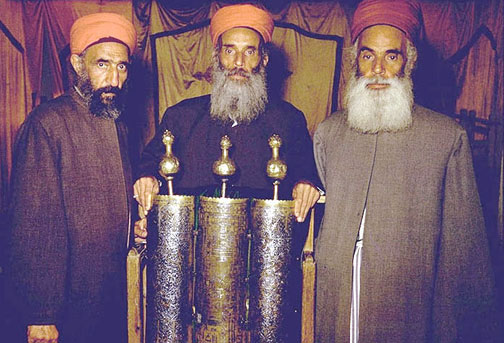

![]() The main tourist attractions of Nablus are

Jacob's Well and the an-Nasir mosque. The mountain

Gerizim is holy for the Samaritans,

while ancient Shechem lies east of the present city.

The main tourist attractions of Nablus are

Jacob's Well and the an-Nasir mosque. The mountain

Gerizim is holy for the Samaritans,

while ancient Shechem lies east of the present city.

![]() 300 Samaritans live near Nablus, which is

about half of their total number.

300 Samaritans live near Nablus, which is

about half of their total number.

HISTORY

20th century BCE: First traces of settlement here.

8th century: As the Assyrians

conquer parts of Israel, Nablus starts to decline. Later,

the Samaritans took over the town.

2nd century: The city is destroyed by the

Maccabean ruler John Hyrcanus.

72 CE: A new city is established by the Roman

Emperor Vespasian, near the site of Shechem. The city is

named Flavia Neapolis, and could thrive from abundant

water supply from springs. Later the city is renamed to

Julia Neapolis.

636: Captured by Arab Muslims.

1099: Captured by the Crusaders, who puts it under

their control, and named it Naples.

1187: Captured by Saladin,

and is returned to Muslim control.

1927: Heavily destroyed by an earthquake.

1930s: Nablus becomes an important centre for Arab

resistance to Jewish

immigration to Palestine.

1949: After the First

Palestinian War, Nablus becomes a part of Jordan. Nablus develops into

becoming a centre for Palestinian military activities

against Israel.

1967 June: Comes under Israeli

control, following the Six-Day War.

1976: Jewish extremists put up a colony on

confiscated Palestinian land.

1995: Comes under Palestinian control, by the

takeover of the Palestinian National Authority.

Information about the City:

Nablus was established in the year 4000 BC and has a very rich history. As a result the city is an archeologist's paradise. The city's economy is based around agriculture and food processing. An Najah University (and it's 10,000 students) can also be found in the city.

http://www.najah.edu/english/aboutnablus.htm.

The heart breaks

http://www.haaretz.com

By Gideon Levy

Na'im Araj awakens every day at 4 A.M., leaves quietly by

the glass door in the living room that leads directly to

the cemetery, and goes to his son's grave, just to be

with him. After sunrise, his brother comes and takes him,

for his own sake, away from there. "Mohammed,

Mohammed," he hears him saying. But even when

they've left the cemetery, glimpses of the dead boy are

everywhere. The crowded camp cemetery is visible from the

window of the house. There in the middle of a row of

headstones, where olive and myrtle branches cover the

freshly turned earth, is Mohammed's grave. The father

need but look out the window to see it. An advantage of

sorts that goes with living in the last house in a

refugee camp, across from the cemetery.

Mohammed Araj was six and a half, and carefully protected

by his father; even on the day he died, he hadn't been to

school, lest something bad happen to him. His father

permitted him to go only as far as the front steps, and

Mohammed did as his father told him. But it wasn't

enough: The soldier emerged from the alley between their

house and the cemetery at the edge of Balata camp, and

shot him once, straight to the heart.

Mohammed was eating a sandwich. Eyewitnesses say the

street was quiet. The sandwich fell down and was covered

with blood. Mohammed somehow got indoors and cried for

his mother, then collapsed in her arms. Afterward, says

the family, the soldiers barred entry to two ambulances

rushing to save the child. The boy's brother, carrying

the bleeding Mohammed, ran, panicked, a few hundred

meters and flagged a passing car. At the hospital, they

could only pronounce him dead. For four days, the IDF

prevented the family from burying their son, because of a

closure.

His father is tormented most of all by the thought that,

if only his son had died in an ambulance, "he'd have

known at least that someone in this world was concerned

for him."

Three front steps lead up to the front door, iron,

painted blue, with two black handprints on it. Mohammed

was shot on these steps as he stood eating his sandwich.

A dim hallway leads to the living room, whence another

door opens out to the cemetery. In the alley opposite

there's a cow barn inside a house. Everything in the

Balata camp is crowded, just like the cemetery, there on

the edge of Nablus.

The living room wall is blank: There is only the picture

of the dead boy, wrapped in a kaffiyeh, above the

computer he left behind. Mohammed, in his blue school

uniform, on his first day of school, less than six months

ago. The picture shows a boy with almond eyes and a sad

look, but they say he smiled often and laughed a lot.

Someone brings the death coat, a checked wool blazer with

a hole in it.

"And afterward they'll talk about `the criminals of

Balata,'" says the camp's ambulance driver, Firas

Abu-Bakri, who in the last few years has seen it all.

"When someone shoots a child in the heart, he knows

where he's shooting. Whoever shot him in the heart knew

he was five or six years old." Abu-Bakri tried to

save the boy, whom he'd known all his life, but the

soldiers wouldn't let him get anywhere near the child.

"It's all lies," says the boy's Uncle Adnan,

his father's brother. "They'll say the soldiers were

fired on and had stones thrown at them, but it's all

lies." Theirs is a Hebrew-speaking home. The child's

father, Na'im, has 15 years' experience working at

Champion Motors in B'nei Brak, waxing Israeli cars

alongside Yigal Shlomi, his friend and today his business

partner, who now telephones daily. Na'im's brother Adnan

worked for 23 years in a factory in Israel. The day the

boy was killed, the soldiers came at night to conduct a

search, and Na'im told them about Mohammed. Adnan relates

that the officer offered his condolences, and that

"he, too, was almost crying."

Stooped, unshaven, his face lined, Na'im enters the room.

On the day before his son was killed, Na'im took Mohammed

along to his little factory instead of sending him to

school. The IDF was in the camp, in an operation

code-named "Tranquil Waters."

"I wasn't afraid something would happen to him, but

I didn't want him to be scared," says the father.

Na'im manufactures hair gel and cleaning supplies. That

day he left his ID card at home so that his wife could

take their daughter to the doctor. An IDF Jeep happened

along and they asked for his ID. "You know how the

soldiers get agitated when you don't have an ID

card."

It was Mohammed who broke the tension. He stuck out his

hand to shake hands with the soldiers. Na'im says that

the officer smiled. "I told him: My son sees no

difference between Jews and Arabs." He believes that

the soldiers who killed his son the next day were the

ones from the Jeep, the ones who shook his hand.

Mohammed hadn't gone to school on the day he died,

December 21, either. In the morning, the boy told his

father that the army was in one of the houses on Na'im's

route to his factory, outside the camp. "Be careful,

Daddy, don't go to work," said the child. Mohammed

wanted a falafel sandwich with tomatoes for breakfast but

the tomatoes in the house were green, Na'im relates, so

he rushed out to buy red ones. That was the next-to-last

meal, the one before the sandwich. Na'im wanted to take

his son with him again to the factory, but Mohammed was

afraid he'd be bored there. He stayed home, to play it

safe. His father left him NIS 5 so he could buy an egg

sandwich for lunch.

At lunchtime, someone came to the factory to buy a gallon

of dishwashing soap, and told Na'im that his son had been

lightly wounded in the arm. At the hospital, he learned

the truth. A little while earlier, he'd seen the IDF Jeep

driving up the road toward his house. From the hospital,

he couldn't go home, because of the closure. He stayed

with his sister for four days, grieving alone, until the

funeral.

Someone brings in a suitcase. All Mohammed's clothing is

folded in the worn brown imitation leather suitcase.

"When you see the clothes, you'll see that he was a

special kid," says the father. Uncle Adnan opens the

suitcase, displaying the neatly folded clothes, and Na'im

breaks down and cries bitterly.

"There's nothing left for me in this life,"

laments Naim. "Everyone knows how I protected him.

Everyone was angry with me for not letting him go to

school. I was bonded to this child. I have another son,

who's 20, who was shot with a rubber bullet a few months

ago. I heard about it and sat right where I was. I said:

If he was shot, he was shot. It's God's will. He knows

how to look after himself. But the little one? My most

beloved child. My model. Like my jacket, that kid. With

me all the time.

"Mohammed knew nothing. He thought the end of the

street through the camp was where the world ended. That

pains me. He was born and didn't even know he was a kid.

He received nothing; only food. He has nothing else. I

can't even sit here for two hours. Nowhere to play,

nothing to do. No child, not a Jewish child nor an Arab

child, deserves a life like this or a death like

this."

Recently his friend, Yigal Shlomi, bought a little live

donkey for Mohammed, so he'd have someone to play with.

One of Na'im's customers, Jacques, met Mohammed at a

checkpoint not long ago and was amazed to see how he had

grown. A child of six, wearing a size 36 shoe, says his

father proudly. Here's a picture from the beach in Tel

Aviv, a long time ago: Mohammed at 18 months, with a

friend from the camp, both of them in swimsuits, the

photo taken by Yigal. And here he is in a camouflage

uniform at the kindergarten graduation party, saluting.

And here's his first, and last, schoolbag. Such a short

life.

Na'im removes a notebook and puts it to his lips,

heatedly, either to kiss it or just to inhale the scent,

the scent of his child. Outside, children are playing

barefoot on this winter day. Abu-Bakri, the ambulance

driver says that on the day the boy was killed, children

were throwing stones just like today; they do it every

day. But Sami, the owner of the grocery store at the

corner of the alley, who witnessed the killing, says that

the street was quiet beforehand. He saw the Jeep come

bursting up the alley and he saw the soldier who got out

of the Jeep ... and fired.

Here's where the soldier was standing when he shot the

boy, maybe 25 or 30 meters from the steps. One bullet to

the heart. Sami says that if the street hadn't been

quiet, he would have closed his shop in a hurry, as he

always does when it gets dangerous. But the shop was

open. A few days ago, the soldiers tore Na'im's picture

of the boy off the window of his car. "They don't

want people to see that picture of a little boy,"

says Uncle Adnan.

The Israel Defense Forces Spokesman's Office responds:

"Following intelligence warnings that five suicide

terrorists were planning attacks in the center of the

country, the IDF has been operating throughout the city

of Nablus, especially in the casbah and the Balata

refugee camp ... In this type of operation, disturbances

often break out involving large numbers of people, which

the terrorists take advantage of to try to harm the

soldiers, using residents as cover ...

"Regarding the incident in question, a disturbance

involving dozens of rioters, who threw firebombs and

rocks at the soldiers, who were in the adjoining building

at the time. After a firebomb was thrown at the soldiers

from the crowd, the soldiers fired warning shots at a

wall far from the place, in order to disperse the crowd

... At no point was a hit on any person identified.

Later, a complaint was received that a Palestinian child

was killed in the incident. The army expresses sorrow for

the death of the child and continues to investigate the

incident."

As for allegations that ambulances were not allowed to

reach the child, the IDF spokesman said this was the

first complaint to be raised regarding this incident, and

"from our perspective, it is unfounded."

..samaritan priests in nablus